The aftermath of the coup is getting all the headlines. But Turkey’s war against the Kurds continues in the shadows.

İSTANBUL — At 7:43 in the morning, Hursit Kulter sent a final message to his family. “I won’t get out,” the Kurdish politician wrote. “Give my greetings to everyone.” It was May 27 — exactly two months ago. No one has heard from him since.

Kulter, a 33-year-old who sports a thick mustache, was a vocal advocate of self-rule for Turkey’s Kurds. His hometown of Sirnak lies some ten miles from the border triangle with Syria and Iraq, countries whose own Kurdish minorities enjoy a degree of political independence.

But the idea of Kurdish self-rule is anathema to the Turkish state, which has fought a bitter war with the autonomy-seeking militants of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) for the past three decades.

Kulter, the Sirnak district administrator for the Kurdish Democratic Regions Party, believed in politics — not weapons — as a means for change.

But as Turkey grapples with the aftermath of a failed coup, its resurgent conflict with the PKK has faded from the headlines. A month ago, security forces were busy “cleansing” Kurdish towns of guerrilla fighters; now, the military itself is being purged of the government’s opponents.

Amid talk of reintroducing the death penalty and allegations of torture, Turkey’s allies fear the country could return to the repression of the late 20th century. But the recent crackdown obscures the fact that the state has already revived elements of that time in the country’s Kurdish-majority southeast.

Kulter’s disappearance in particular raises the specter of a return to Turkey’s darker past: In the 1990s, when the conflict between the state and the PKK reached its bloody peak, hundreds of Kurdish civilians vanished at the hands of security forces.

Sometimes, a body would be found weeks or months later. But many families still search for information about their loved ones twenty years later, clinging to the hope that they will return alive.

“It’s the most difficult thing,” said Kamil Kulter, Hursit’s elder brother. “If someone dies, you receive his body. You bury him. But we don’t know what happened to him, whether he’s alive or not, whether he’s in prison or not. Hope is the worst thing.”

On the day of Kulter’s disappearance, a Twitter account believed to be linked to special forces operating in the southeast tweeted that he had been arrested. Then the account posted another tweet:

“Hursit Kulter, who declared self-rule in front of the cameras, asked for blessings in a sewage ditch. Now he is in hell.”

Quoting two eyewitnesses, local Kurdish media reported that Kulter had been arrested by special forces and put into an armored vehicle, but local authorities and security forces deny taking him into custody.

“It fits the United Nations’ definition of an enforced disappearance,” said Melis Gebes, a lawyer working for the Istanbul-based Memory Center, which has documented nearly 500 such cases. Kulter’s disappearance fits a pattern, she added: “People have seen him being taken into custody but all officials are denying he was detained. Usually there is no effective investigation, either.”

After a social media campaign demanding information about Kulter’s whereabouts gained traction last month, the interior ministry sent an investigator to Sirnak, but the family say they have seen no progress. The local courts did not respond to the family lawyer’s request to open a case.

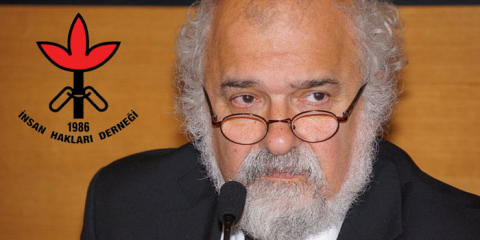

“We thought the disappearances from the 90s had restarted, so we ended up applying to the U.N. committee for missing people,” said Seyma Urper, a lawyer for Turkey’s Human Rights Association who is working with Kulter’s family.

Kulter’s disappearance is the first such case in Turkey since 2004. The vast majority of the estimated 1,000 civilians who vanished in custody did so in the 1990s; the Memory Centre has documented only four cases since 2000.

After years of relative calm, a shaky two-year-old ceasefire between the PKK and the state collapsed last summer. As the group resumed attacking police and military installations and Turkey began bombing its camps in northern Iraq, local citizens’ assemblies declared autonomy in southeastern cities, drawing the ire of the state. Among those calling for self-rule was Hursit Kulter.

The call was taken up by the PKK’s youth wing, whose members began digging trenches and setting up barricades in several towns. In response, the military placed the towns under blanket curfews lasting months while trying to flush out the fighters.

In the ensuing clashes, neighborhoods turned into urban war zones. Security forces moved against the militants with snipers, tank fire and heavy artillery. The curfews became de-facto sieges as residents became trapped in their houses; the International Crisis Group has counted at least 307 civilian deaths in the past year.

Sirnak — the city where Kulter lived and where he was when he disappeared — has witnessed some of the worst violence.

It has been under military lockdown for months amid fierce clashes between security forces and Kurdish militants. Images taken during the lockdown show a ghost town destroyed by war: collapsing buildings, burnt-out houses and rubble-strewn streets. The city’s mayor estimates that at least 60,000 of its 63,000 inhabitants have left.

When the military announced the current curfew in mid-March, thousands fled the city in a single day, but Kulter decided to stay behind, insisting it was a politician’s responsibility to stay with his people. He hid in his aunt’s house amid violent clashes, sending sporadic updates to friends and family.

On the morning of May 27, however, he sent his brother a series of hastily written WhatsApp messages, including a farewell phrase that roughly translates to asking for forgiveness, implying that Kulter expected to die.

His family still has hope that he will return. Describing his younger brother in a phone call from an IDP camp near Sirnak, Kamil Kulter switched back and forth from present to past tense: “He’s a warm, affectionate person. Almost all the people in Sirnak knew Hursit and loved him. Our hope is that he will come back alive, but if not, we will fight for justice until the end,” he said.

Yet calls for justice for Turkey’s missing have often fallen on deaf ears. During a visit in March, a U.N. human rights delegation condemned Ankara for failing to investigate past disappearances, criticizing the “palpable lack of interest to seriously investigating and adjudicating these cases.”

Human rights organizations have reacted with alarm to a new law granting counter-terror forces immunity from prosecution. Similar laws in the 1990s “contributed to the systematic impunity enjoyed by security forces despite… extra-judicial killings, enforced disappearances, torture, and the unlawful destruction of thousands of homes,” Human Rights Watch warned earlier this month.

Following the July 15 coup attempt, the country’s rule of law faces further erosion. The judiciary has been purged of 3,000 judges and prosecutors, and its independence hangs by a thread. Amnesty International has documentedtorture — even rape — of military personnel arrested in the post-coup crackdown.

As Turkey is busy purging state institutions of suspected coup supporters, Kulter’s case has fallen off the government’s list of priorities, raising fears that his disappearance may remain unresolved like so many others.

In the absence of political will to hold Turkey’s security forces accountable, the families of the disappeared have refused to remain silent. Every Saturday at 12pm, a group of relatives sits down in Istanbul’s busy Istiklal Avenue with portraits and red carnations to hold a vigil for their missing.

The Saturday Mothers, as they are known, have gathered more than 500 times since 1995.

On the first Saturday of July, the Mothers held up a new portrait. Among dozens of yellowed prints and black-and-white images, it stood out as the only photograph taken in the past two decades. “Interior minister Efkan Ala, tell us,” a woman shouted. “Where is Hursit Kulter?”