Brazilian Truth Commission: a delayed effort

In May of 2012, President Dilma formally inaugurated the truth commission, which will have two years to prepare a report on human rights abuses within the framework of its mandate. In this regard, we decided to research the history of Brazil's military dictatorship and examine their efforts to reckon with this past.

|

A protest before the statue of President Castelo Branco, who was the Junta's first President, Rio de Janeiro Photos: Henrique Fornazin ve Amy Jo Westhrop, 29 Temmuz 2012 |

What happened?

In 1964, the Brazilian military, right-wing politicians, and the US Government developed concern over the increasingly leftist policies of President João Goulart (popularly known as Jango) and his purported closeness with several communist governments like Cuba. As a result, the US provided support to and fomented a coup that ended with Goulart’s resignation (and exile) and the establishment of a military regime under the presidency of Marshal Castelo Branco presidency that was to remain in power until 1985. The Brazilian military government, in its attempt to consolidate and centralize power, systematically used brutal methods of torture to intimidate its political opponents and to discourage popular political activity. In 1968, the government of President Artur da Costa e Silva, an army general appointed to the presidency, wrote a new constitution that institutionalized the dictatorship as it expanded the executive branch and silenced the legislative branch. One of the primary goals of the military regime was the economic growth of Brazil through the temptation and attraction of foreign investment. Consequently, the time between 1969 and 1973, during which Brazil’s economic growth rates averaged around 10%, has been termed the ‘Brazilian Miracle.’ This era of authoritarian technocracy was also the era during which repression reached its peak. The Brazilian president, through a new law, gained the ability to suspend the National Congress, intercede in states affairs, and suspend habeas corpus and other individual rights. Oppression in universities and aggressive censorship of the press skyrocketed during this time, and the numbers of arrests, torture, and disappearances rose sharply as well. The aggressive nature with which the government outlawed leftist movements and ideology polarized leftist activists and led to their radicalization. Most of the guerrilla resistance movements against the military regime, therefore, were borne out of the Brazilian Communist Party that disbanded in 1962 over factionalization concerning revolutionary strategy. In the era of the aforementioned ‘Brazilian Miracle,’ the oppression served to galvanize opposition and resistance groups.

An insufficient effort: unofficial commission of inquiry

Amidst growing pressure from civil society organizations and associations of family members of victims of the regime, in the late 1970s, the military regime passed the Law of Amnesty. This law, which allowed for the return of exiled Brazilians and the release of a number of political prisoners, however, also served to give impunity to the perpetrators of violations. Therefore, even though amnesty was originally a step in the transition to democracy, it has since stymied efforts to understand and reckon with Brazil’s violent history. There have been a number of transitional justice mechanisms implemented in the process of democratization. The 1985 unofficial commission of inquiry organized and funded by the World Council of Churches, was made possible—ironically—by the 1979 amnesty laws that opened up the government’s archives of military trial transcripts and other files. Lawyers were permitted to access to the archives to prepare amnesty petitions on behalf of their clients and could check out the files for 24 hours. Lawyers could check out the files in the archives for 24 hours at a time in order to prepare their clients’ amnesty petitions. Under this pretense, the researchers systematically and painstakingly copied every page of the files until the entire archive had been duplicated. Additionally, lawyers obtained statements from 1,843 prisoners who asserted that they had suffered rights violations and torture while being tried by a military tribunal. Methodologically, the commission examined the discrepancies between the laws as written and the conclusions of the court proceedings to articulate the the report that this effort generated,Brasil: Nunca Mais, is the most comprehensive account of human rights violations in Brazil: all in all, the commission collected over 2,700 pages of testimony, documented close to 300 different kinds of torture, and identified approximately 17,000 victims, and the full report (called ‘Project A’) amounts to over 7,000 pages. However, because the project was unofficial, and because of the 1979 amnesty law, the project was incapable of providing reparations, pursuing justice, or making judicial recommendations.

Acknowledgement of disappearances

In 1995, the Brazilian government passed a law that acknowledged the deaths of 136 people during the era of the dictatorship. In addition, the law created a framework for the disbursement of reparations to victims and their families. The law also created a ‘Special Commission on Political Deaths and Disappearances’ (CEMDP) that, in its 2007 report, acknowledged state responsibility for violations, documented nearly 500 cases of forced disappearance, and initiated reparations for 300 families afflicted by the conflict. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva announced in 2009 the establishment of the National Human Rights Plan (PNDH), which would ostensibly revoke the 1979 Amnesty Law and create a truth commission to investigate human rights violations during the military dictatorship. Naturally, chaos erupted within the government, and several ministers and military officials threatened resignation, claiming that the PNDH was unfairly biased against the military rulers and exonerating the resistance movement’s crimes. Though President Lula promised to reassess the mandate of the proposed truth commission, it did not come to fruition during his time in office.

The Truth Commission launches

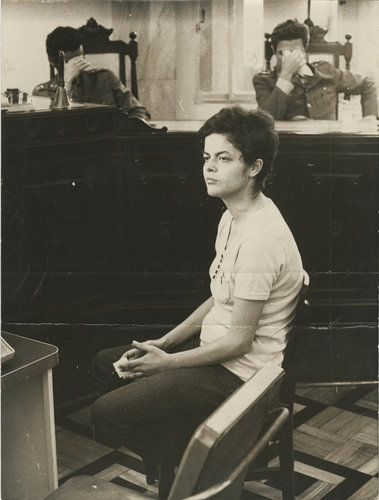

|

Dilma pictured at 22 in a hearing in 1970. The commission will also investigate the torture she experienced. Photo: Adir Mera, Public Archive of the State of São Paulo. |

With the swearing in of President Dilma Rousseff—a former guerrilla who was imprisoned and tortured, and who campaigned on a platform of bringing human rights violators to justice—in January 2011 came renewed vigor concerning the idea of a truth commission. Nine months later, in October, Congress finally passed the National Truth Commission(Comissão Nacional da Verdade) bill after several amendments that changed the mandate, structure, and authority of the truth commission. In May of 2012, President Rousseff formally inaugurated the truth commission, which will have two years to prepare a report on human rights abuses within the framework of its mandate. The main aims of the commission are stated as necessity to fulfill “the right to truth and true history” and to promote “the national reconciliation.” The commission has been given the authority to examine and investigate violations that occurred between 1946 and 1988, in order to avoid incriminating merely just the military. Composed of seven members, all of whom are appointees of President Rousseff, the commission will not have the authority to prosecute perpetrators or members of the military regime. Rather, it will leave the 1979 Amnesty Law in place and will not have any legal standing. The commission will enjoy a great investigative competence unlike its precedents in Latin America. In this vein, document-based research will look not only at classified/top-secret files within the Brazilian government, but will also look at declassified documents from the US State Department and the CIA to fully understand America’s role in the 1964 coup. Some issues about the commission remains controversial and, in some ways, ambiguous. Firstly, its mandate even is not clear among the members of the commission. One of the commissioners, lawyer Rosa Cardoso, has stated that the commission will not look at crimes committed by the resistance movements, while another commissioner, however, former justice minister José Carlos Dias has publicly contradicted this statement. Another discussion rose because ineffectiveness of the commission against the impunity. The Amnesty Law de jure guarantees the impunity of the perpetrators of mass abuses during the dictatorial era. Retired officers and members of the military have censured the commission because none of its seven members are military officials. Interestingly, the creation of the truth commission came at a moment when public opinion regarding the armed forces was at historically high levels in Brazil, raising the question of what is at stake and who will benefit from the commission. At present, it is too early to know what exactly this truth will mean for the future of Brazil.