Murat Çelikkan: When dissent becomes crime

Yazan: Krizna Gomez, Dejusticia

Published in: El Espectador

20 August 2017

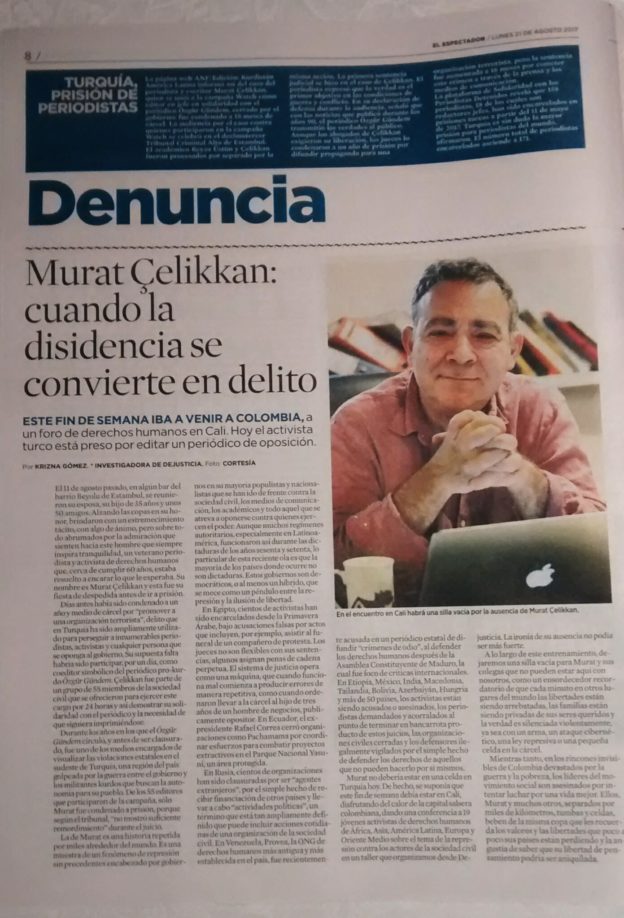

This weekend he was supposed to come to Colombia, to a forum on human rights in Cali. Today the Turkish activist is in jail for being editor of an opposition newspaper.

On August 11, in a small bar somewhere in the Beyoğlu neighborhood of Istanbul, 50 or so friends, his wife and 35-year old son gathered one last time, each one raising their glasses to him. They clasped their drink with an unspoken shudder, tinged with encouragement but mostly overwhelmed with admiration for this man—a veteran journalist and human rights activist in his late 50s, bespectacled and gentle in his manners, resolute and calm in the future that was awaiting him. This man was Murat Çelikkan. And this was his send-off gathering to prison.

Several days earlier, he was sentenced to one and a half years in jail, for the crime of “propagandizing for a terrorist organization”, which in Turkey today has been widely used to persecute countless journalists, activists and anyone who oppose the government. His supposed wrongdoing was being a symbolic Co-Editor for one day for the pro-Kurdish newspaper Özgür Gündem. There were 55 other members of civil society who volunteered to this Editor-in-Chief on Watch campaign at that time, which was launched to show solidarity to the paper’s work. In the many years of operation of Özgür Gündem, which now has been shut down, it has brought to light government violations in Southeastern Turkey—a part of the country that has been battered by war between the government and Kurdish militants seeking autonomy for the ethnic minority. Of all the 55 acting editors, only Murat was sentenced to jail time, because according to the court, he “did not show sufficient remorse” during the trial.

Murat’s story is only one of thousands around the world today, in what has been an unprecedented wave of crackdown by governments, mostly populist and nationalistic, against civil society, the media, academics and other opposition actors that dare to dissent against the government. While many authoritarian regimes, especially here in Latin America, have done this especially during the dictatorship years of the 60s and 70s, the unique thing about this current wave is that most of the governments involved are not dictatorships—they are democracies, or at least a hybrid of them, swinging like a pendulum between repression and trappings of freedom.

Krizna Gomez’s article was published on August 20 in El Espectador, one of the leading daily papers in Colombia .

In Egypt, hundreds of activists have been thrown into jail since the Arab Spring, on trumped up charges for acts that include attending the funeral of a fellow protester. Judges don’t go light on their sentences—some would hand down life sentences—and have been processing cases like a factory machine that has seen mistakes like sentencing to jail the three-year old son of a businessman who is known to oppose the government. In Ecuador, ex-president Correa shut down organizations such as Pachamama, for leading efforts to fight his extractive projects in the protected Yasuni National Park. In Russia, hundreds of organizations have been closed for being “foreign agents”, for the sheer act of receiving foreign funding and conducting “political activities” that is so broadly defined that it can include activities that would normally be part of the daily work of a civil society organization. In Venezuela, Provea, the oldest and most established human rights NGO in the country, was recently accused of spreading “hate crimes” in a state newspaper for advocating for rights after Maduro’s widely-criticized Constituent Assembly. In Ethiopia, Mexico, India, Macedonia, Thailand, Bolivia, Azerbaijan, Hungary, and more than 50 other countries, activists are being harassed or killed, organizations shut down, journalists sued to bankruptcy, and advocates being surveilled illegally for the sheer act of fighting for the rights of those who cannot.

Murat was not supposed to be sitting in a jail cell in Turkey today. In fact, he was supposed to be in Cali, soaking in the gentle heat of this salsa capital, giving a lecture to 19 young human rights activists from Africa, Asia, Latin America, Europe and the Middle East on the topic of crackdowns against civil society actors in a training that we at Dejusticia organized. The irony of his absence could not be starker.

Throughout this training, we leave an empty chair for Murat, as well as his colleagues who could not be here with us, as a deafening reminder that freedoms are being snatched away in other places in the world by the minute, families are being deprived of their loved ones, and truth that is waiting to be told is being silenced with the use of a gun, a cyber attack technology, a repressive law, or a small jail cell.

Closer to home here in Colombia, in unseen corners of the country long ravaged by war and poverty, social movement leaders get killed for attempting to fight for better lives. They, Murat, and countless others, separated by thousands of miles, graves and jail cells, sip of the same cup that reminds them of the values and freedoms that their countries are slowly losing, and the free mind that might one day become extinct.