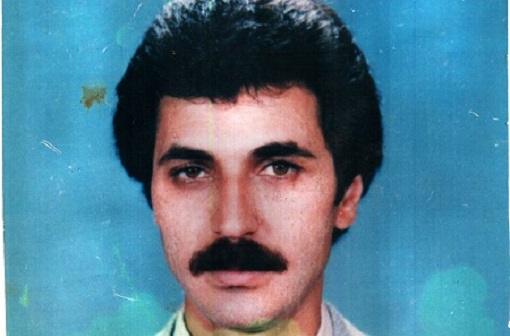

Enforced disappearances and the Constitutional Court: An evaluation of the judgment on the Hasan Gülünay Case

Lawyer Melis Gebeş evaluated the Constitutional Court’s judgment dated 21 April 2016 on the case of Hasan Gülünay, who was forcefully disappeared on 20 July 1992. She stated that in its judgment, the Constitutional Court did not take into consideration the European Court of Human Rights’ (ECHR) established case-law on enforced disappearances. The Court’s judgment on the Hasan Gülünay case, which has been recently submitted to the ECHR’s attention, is especially important, as it is the first judgment of the Constitutional Court on enforced disappearances that has been sent to the ECHR. Hakikat Adalet Hafıza Merkezi, (engl. Truth Justice Memory Center) had submitted a legal opinion in the form of “amicus curiae” brief on Hasan Gülünay’s enforced disappearance and published the opinion last year.

Melis Gebeş from the Legal Studies Program talked about the importance and content of amicus curiae on 12 May 2016 on Burcu Karakaş’s TV program “Hak İhlalleri Karnesi.” (eng. Right Violations Report)

Melis Gebeş, Hafiza Merkezi Memory Studies Program

The recognition of the right to lodge individual applications to the Constitutional Court has opened up a new legal avenue for fighting impunity of enforced disappearances. [1] Up to this date, the Constitutional Court has made judgments on five of the individual applications on enforced disappearances.[2] The Court ruled that the individual application on Nurettin Yedigöl’s enforced disappearance is inadmissible because of the Court’s incompetence ratione temporis, whereas for other individual applications, the Court ruled that the public authority has violated basic rights and freedoms. A number of individual applications on enforced disappearances are still waiting for the Court’s examination.

One of the most important rationales behind the recognition of the right to lodge individual applications to the Constitutional Court is to decrease the number of applications to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) and respond to human rights violation complaints on the national level. [3] For this reason, to make individual applications an effective remedy at the domestic level, the Constitutional Court has to interpret the provisions of the Constitution in line with the European Convention of Human Rights with a consideration of the ECHR’s case-law when making judgments. On the other hand, the non-conformity of the judgments of the Constitutional Court to the established case-law of the ECHR on enforced disappearances leads to discussions about whether the individual applications are an effective remedy or not. There are concerns about the Court’s future judgments on the remaining cases of enforced disappearances.

One of the fundamental criticisms of these judgments are about the Constitutional Court’ conclusion that there was only a violation of the requirement to conduct an effective investigation, which only constitutes the procedural aspect of the right to life; and contrary to the ECHR’s case-law, the Court did not take into consideration complaints concerning the prohibition of torture or the right to an effective remedy. Moreover, it can be argued that the failure of the Constitutional Court in following the standards of proof adopted by the ECHR concerning enforced disappearances prevented the Court to conclude that the right to life was violated based on substantive requirements. Furthermore, even though the Constitutional Court ruled that the requirement to conduct an effective investigation was not met, the Court did not provide an effective remedy to reverse the consequences of the violation.

An important example to this is the judgment given in 2016 in response to an individual application made in 2013 by Birsen Gülünay, the wife of Hasan Gülünay who was forcefully disappeared in 1992 in Istanbul. Even though the judgment states that the requirement to conduct an effective investigation was not met, the Constitutional Court did not send the case to a prosecutor in order to force an effective investigation while stressing that a new investigation cannot be opened because the limitation period has passed. The judgment on the Hasan Gülünay case, which provides us important clues in order to assess the conformity of the newly developing case-law of the Constitutional Court on enforced disappearances to the ECHR’s case-law, was also submitted to the ECHR for an evaluation. This is also important as it has become the first ECHR application, which was done following a Constitutional Court judgment on enforced disappearances. The following article evaluates the judgment based on the ECHR’s established case-law concerning admissibility, substance and procedures.

Admissibility

The admissibility rules of the Constitutional Court, as well as the ECHR, state that individual complaints made to these courts are of secondary importance. Claims of right violations should be first solved through first instance courts. Both courts require the applicants to give the necessary attention to the subject as a precondition of admissibility. In its discussion of admissibility of the Hasan Gülünay case, the Constitutional Court stated that the application is admissible because the applicant Birsen Gülünay has shown diligence in exhausting all legal remedies except the Constitutional Court. This is a positive aspect of the judgment.

The Public Prosecutor of Istanbul opened the first investigation on Hasan Gülünay’s enforced disappearance in 2009, years after the event, upon the complaint of Birsen Gülünay. Even though, Birsen Gülünay had made an oral complaint to the Istanbul State Security Court (SSC) before, no investigation had been carried out as a result. There is only an investigation committee report prepared upon her complaint to the Grand National Assembly of Turkey in 1992.

The Constitutional Court, which discussed the claim that whether Birsen Gülünay ″has not shown diligence in her duty to exhaust all legal remedies since she had not been active for a long time,″ stated that even though she made a complaint to the Istanbul SSC and did not provide a documentary proof of the court’s reply, this would not result in the inadmissibility of the application.

Stating that applicants do not have to file an official complaint as part of their obligation to act with diligence, the Constitutional Court concluded that informing public authorities on these claims is sufficient to initiate an ex-officio investigation. According to this statement, with Birsen Gülünay’s complaint to the General Assembly and her request of information from the General Directorate of Security, public authorities are considered informed about these claims. For this reason, even though there are no documents showing an official complaint that was made to the prosecutor, it is not possible to say that Birsen Gülünay did not act with diligence while she was seeking remedy.

Right to Life – In Terms of Substance

Stating that the state cannot be responsible for the disappearance of Hasan Gülünay, the Constitutional Court ruled that the right to life was not violated based on the substantive requirements. The Court held that that it cannot be proven beyond reasonable doubt that Gülünay was taken into custody by state officials and there was no sufficient evidence with concrete elements to support that he was dead.

Even though the ECHR adopts standards of proof beyond reasonable doubt as a rule, it makes changes on these standards in cases of disappearance because of the nature of such cases, which involves the perpetrators’ denial. In cases where the evidence is inaccessible to applicants, the court is satisfied with secondary evidence to confirm the truth of the claims. It may base its decision on sufficiently strong, clear and concordant inferences or of similar unrebutted presumptions of fact.

For instance, in its judgment on the case of Mehmet Özdemir, who was taken into custody without the knowledge of his relatives and have not been heard of since, the ECHR used as secondary evidence Mehmet Özdemir’s alleged involvement with the illegal organization and him being a wanted person, along with authorities’ failure to investigate his wife Enzile Özdemir’s complaints, despite their refusal to confirm that Mehmet Özdemir was taken into custody or to make any statements regarding his abduction or murder. Finding the applicant’s version of facts as constant, save for minor details, the Court ruled that the applicant’s submissions regarding the facts are credible.

Although the ECHR concluded that the Court is unable to draw a complete picture of the factual circumstances surrounding Mehmet Özdemir's disappearance due to the defects in the domestic investigation and the absence of his physical remains, it nevertheless has found that there are strong inferences, based on concrete elements, on which it may be concluded that Mehmet Özdemir was apprehended and taken into custody as alleged and disappeared thereafter. (Enzile Özdemir/Turkey, B. No: 54169/00, 08.01.2008, §§ 45-48)

Having a similar line of reasoning in its judgment on the case of Ahmet Çakıcı, who was taken into custody without the knowledge of his relatives and have not been heard of since, the ECHR Commission pointed out that very strong inferences may be drawn from the authorities’ claim that Ahmet Çakıcı’s identity card was found on the body of a dead terrorist. The ECHR has found that there is sufficient evidence on which it may be concluded that Ahmet Çakıcı died following his apprehension and detention by the security forces. (Çakıcı/Turkey, above-mentioned, § 85).

Similarly, there are strong, clear and concordant inferences which are sufficient to prove that Hasan Gülünay was taken into custody by the security forces and died under their supervision. A person, who has called Hasan Gülünay’s office phone from the Anti-Terror Branch, has told that Gülünay was under custody. Moreover, Gülünay was sought after because he was under the suspicion of having committed acts that require criminal investigation, in the name of an illegal organization. His identity was found on Ali Ekber Atmaca who was later caught because of his alleged involvement with an illegal organization and killed under torture. Birsen Gülünay’s complaints were not taken into consideration even though the authorities did not make any sufficient and credible statements on the fate of Hasan Gülünay.

On the other hand, contrary to the ECHR’s case-law, the Constitutional Court stated that it should be proven unequivocally that Hasan Gülünay was taken into custody. Noting that there are no witness statements that may prove that Hasan Gülünay was taken under custody except the custody records and the statement of the applicant, the Court ruled that the secondary evidence do not prove beyond doubt that Hasan Gülünay was taken into custody.

Right to Life – In Terms of Procedure

The Constitutional Court ruled that the state failed to carry out an effective criminal investigation in violation of the procedural requirement of the right to life. Even though this conclusion is positive, the Court’s failure to force for the reopening of the investigation in order to remedy the consequences of the violation points out to the failures of the judgment. The expiration of the limitation period of the investigation was effective in the Court’s decision to not to reopen the investigation.

The failure of public authorities to instigate an ex officio investigation to determine Hasan Gülünay’s fate and identify the perpetrators of the crime is one of the reasons behind the Court’s judgment that there was a failure to conduct an effective investigation. In cases such as this one where there is a lack of information on how the event has occurred and who the perpetrators are, the investigating authorities’ failure to conduct reasonably diligent and prompt investigations, for example their failure to listen to the witnesses even though it is difficult to remember what has happened after an amount of time, is also among the reasons behind this decision.

Moreover, according to the Constitutional Court, the fact that the information given by the security forces was seen as sufficient and the reliability of this information has never been questioned show that the investigation was not carried out in an objective and careful manner. Besides, it is apparent that the custody records presented by Hüseyin Kocadağ cannot be deemed reliable since he was killed at the Susurluk car accident, which revealed an organization within the law enforcement agency that was responsible for grave violations of human rights, including illegal and arbitrary killings, and enforced disappearances. The investigation was held in abeyance for a long time without any actions that would yield results and ended with the expiration of the limitation period, all of which point out to the failure to conduct an effective investigation.

Yet the Constitutional Court refused the argument that the crime committed against Hasan Gülünay is among the crimes against humanity defined in the Article 77 of the Criminal Code, therefore cannot be subject to any statutory limitations. Adding that the Criminal Code that was in force when the crime was committed should be applied because it is in favor of the accused, the Court has not found the application of statutory limitations unlawful according to the Criminal Code of the time.

Similarly, the Article 7 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms states that no one shall be held guilty for an act that did not constitute an offence at the time when it was committed. This article regulates the principle of legality which is a universal principle. On the other hand, the second paragraph of the article defines an exception to the rule. According to this, an act that is considered an offense according to the general principles of the law can be prosecuted even though they are not under legal regulation. The ECHR clearly states this principle in its Korbely v.Hungary and Kononov v. Lithuania judgments. The Court ruled that crimes against humanity, irrespective of whether they are punishable under domestic law of any country, shall be prosecuted since the responsibility of the perpetrators existed under international law. (See. Kononov/Lithunia, B. No: 36376/04, 17.05.2010 and Korbely/Hungary, B. No: 9174/02, 19.09.2008)

Even though enforced disappearances are not categorized as an offense under contemporary laws as well as laws that were in effect when the crime was committed, the international law doctrine and case-law qualify enforced disappearances as a crime against humanity and thus they are not subject to a statute of limitations. For this reason, it is not possible to say that the Turkish courts, including the Constitutional Court, applied the principle of legality in compliance with the law.

Conclusion

The judgment on the Hasan Gülünay case gives an idea about the future conduct of the Constitutional Court concerning individual applications on enforced disappearances. Even though the judgment has its positive aspects, it does not reflect the established case-law of the ECHR on enforced disappearances. It does not meet the requirements of international human rights law concerning the application of the statute of limitations. The position of the Constitutional Court makes it difficult to consider the Court as an effective legal remedy for individual applications on enforced disappearances in the future.

Even though the Constitutional Court ruled that the failure to conduct an effective investigation resulted in the violation of the procedural requirement of the right to life, it fails short in remedying the consequences of the violation. The Court stated that a new investigation of the enforced disappearance of Hasan Gülünay could not be opened because the limitation period has passed. On the other hand, because of the violation of the requirement to carry out an effective investigation, which led the Court to conclude that the right to life was violated, information is still missing on the fate of Hasan Gülünay, the reasons of and the conditions surrounding the violation or the identity of the perpetrators. The hindering of the search for the truth about Hasan Gülünay with the application of the limitation period does not comply with international human rights law. When it is known that one of the most common obstacles in the fight against impunity in enforced disappearances in Turkey is the application of a limitation period, it is unacceptable that the Constitutional Court adopts the same practice.

[1] The right to lodge individual applications to the Constitutional Court was recognized with the Law No 5982 Amending Certain Provisions of the Constitution which went into effect as a result of the referendum held on 12 September 2010.

[2] The judgment dated 21/4/2016 made as a result of the individual application no: 2013/2640 lodged by Birsen Gülünay on the enforced disappearance of Hasan Gülünay; judgment dated 21/4/2016 made as a result of the individual application no: 2013/7832 lodged by Hıdır Öztürk and Dilif Öztürk on the enforced disappearance of Ayten Öztürk; judgment dated 18/5/2016 made as a result of the individual application no: 2014/14583 lodged by Maşallah Güzelsoy on the enforced disappearance of Sedat Güzelsoy; judgment dated 16/6/2016 made as a result of the individual application no:2014/4038 lodged by İsak Tepe on the enforced disappearance of Ferhat Tepe; judgment dated 10/12/2015 made as a result of the individual application no:2013/1566 lodged by Zeycan Yedigöl on the enforced disappearance of Nurettin Yedigöl.

[3] See the Reasoning for the Law no: 5982, Article 19.

Related links: Truth Justice Memory Center (Hafıza Merkezi)published its “Amicus Curiae Report on Enforced Disappearances² which was addressed to the Constitutional Court as an amicus curiae brief regarding the enforced disappearance of Hasan Gülünay. Melis Gebeş from the Hafıza Merkezi Legal Studies Program talked about the content and importance of the amicus curiae on Burcu Karakaş’s TV program “Hak İhlalleri Karnesi.” (eng. Right Violations Report) Please click to watch.