Murat Çelikkan

My maternal grandmother was born in 1901. She used to claim that her sister Nuriye had changed her age so that she could sell the inheritance from their father Ridvan Pasha. But still on the identity card, which is in my possession now, the year is 1901. As the family members passed away their family albums, personal letters, their identification cards, their marriage certificates from generation to generation ended up with me. These family albums go back to the mother and father of my maternal grandmother and my mother’s grandfather Recaizade Ekrem (B. 1847) and even to his father Recai Efendi The Mad.

To tell you the truth I was not interested in my family history till my father and mother died. Since my mother told me in primary school that I should not talk about the fact that the first novelist of the Ottoman era Recaizade was my grandfather because it was not appropriate to talk about such things, I did not care about where I came from or who we were, etc.

Identifying myself as a communist during my youth and a good part of my mature life also had an impact on this too. It was meaningless to remind others about your class while you were struggling for a class that you did not belong to. And furthermore it was class not ethnicity that mattered in that philosophy. That is why I was not interested in the Circassian origins of my father. Being Circassian meant only the Circassian chicken, pılpılçıka, the Circassian cake and the Circassian folklore for me – and also my paternal grandmother’s curses in the Abkhazian language when she was angry.

But maybe because there is no family member remaining to answer my questions about the family histories, I started to have questions about my grandparents, the family history and even about my mother and my father. I then started to try to get the answers from the family albums. In a gesture, in a stare, in the clothes that they were wearing, in the surroundings…

I went to New York last year for a semester to Columbia University to participate in a fellowship program on Historical Dialogue. Apart from the fellowship program, I wanted to attend two additional courses, but the professors had to accept your attendance to their classes. One professor was Menachem Z. Rosensaft. He was giving a class on The Law of Genocide at the Law Faculty of Columbia University. Professor Rosensaft was the founder of International Network of Children of Jewish Survivors and the sibling of the survivors of two concentration camps Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen. He was a well known name in the field of law of genocide as well as being a columnist for the Huffington Post. He accepted me and three colleagues from the region of former Yugoslavia. Throughout the semester we went through the Nurnberg Trials, then the International Tribunal for Rwanda and Yugoslavia, The Genocide Convention, the Eichman Trial, Crimes Against Humanity, War Crimes, Sexual Crimes even Fascism and Racism… It was a lifetime experience to take that course.

The course started with the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948) – and of course with the Armenian Genocide. Because Raphael Lemkin, who prepared and lobbied for this convention had based it on the Armenian Genocide and had used the word genocide for the first time in an article about the Armenian and Assyrian Genocide. I had to answer quite a few questions being the only person coming from Turkey in the class. I had to explain why after 100 years of the genocide The Turkish Government still denied it. Then it was my Serbian and Croatian colleagues’ turn to answer about a more recent genocide and its denial, Srebrenica. To sum it up, I would like to remind the reader that everywhere in the world a course on genocide and crimes against humanity starts with the Armenian Genocide. Of course except for Turkey! (Most probably Azerbaijan too.)

So this brings us back to the second course I wanted to attend. The name of the course was Armenian Literary and Artistic Responses to the Genocide of 1915. The course was given by a philosophy professor, Armen Marsoobian. I applied but was unsuccessful to get an acceptance. Not because Armen did not want to have a Turkish citizen in his class. Not because he had doubts as the Mothers of Plaza De Mayo in Buenos Aries. Because when we went to meet them to discuss enforced disappearances the first thing they asked us was: “We want to know about your position on the Armenian Genocide before we agree to discuss with you”. It was only because Armen was giving lectures one semester at Columbia University and one semester at the Southern Connecticut State University. And this was the wrong semester for Columbia. But he wanted to meet me.

We did meet. At the beginning of our long conversation Armen and I talked about art, Turkey, about Merzifon and Sivas. Those regions were the homeland of his ancestors and they were the founders of one of the pioneering photography studios in Anatolia. They had survived the Genocide by converting to Islam, but gave shelter to a lot of Armenians in the basement of their house who tried to flee. During the conversation, mentioning Osman Kavala’s name, he told me that he was planning to have en exhibition with an NGO, Anadolu Kültür, in Istanbul. ‘The world is definitely small’ I thought. Osman was a close friend and my wife was the director of Anadolu Kültür. And still I did not know about the plans to have this exhibition.

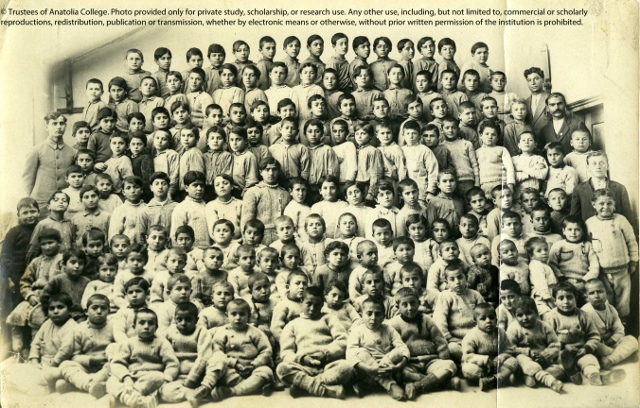

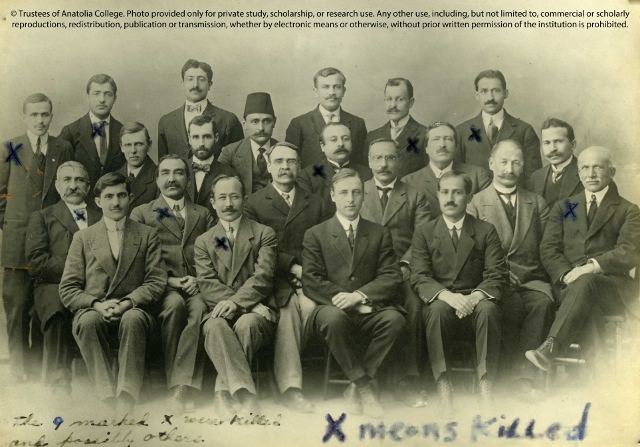

One of his grandparents was Tsolag Dildilian, the founder of the Dildilian Brothers studio. Their archive of about 600 original photographs and their memoirs were in Armen’s possession now. We looked through those photographs of early 20th century Anatolia, they were digitalized and we could go through them in Armen’s laptop. I was impressed, because there weren’t many resources about life in Anatolia at the turn of the century except for the official version.

But still one thing did not occur to me at all! Until the panel discussion on the 26th of April 2013 in Istanbul at DEPO where the exhibition of “Bearing Witness To The Lost History of An Armenian Family – Through The Lens of The Dildilian Brothers” was launched on the 25th of April 2013. At the panel discussion about the exhibition the panelists were Armen T. Marsoobian, Arsinée Khanjian and Ayşe Gül Altınay and the moderator was Salpi Ghazarian. Let me recite what Arsinée Khanjian, a famous international actress, said from memory: “I was astonished when I met Armen and saw his collection. I have collected books, memoirs, photographs of Armenians during my travels to different countries. I was born in Lebanon and photographs of my grandparents do not exist. With what I had collected I tried to build up an Armenian past. The past as for many Armenians and me is something you reconstruct by thinking and visioning. But Armen’s collection is not only witnessing his family history but is also a witness to almost all the Armenians’ past.”

Yes I had taken courses, participated in debates, made speeches about it but never thought that what was lost was not only the Armenian people, it was also a history and its documents.

Having family albums has a class issue to it of course. My mother’s side being bourgeois and my father coming from the rural parts has an impact on the matter of the misbalance of family albums on my maternal and paternal sides. But this does not change the fact that the lack of family albums and photographs on my father’s side was at the same time because they had come to Turkey with the enforced Circassian immigration; that they also left their memories, language, belongings in their homeland to save their lives.

No, the Armenians could not have family albums dating back to the turn of the 20th century. Those few who survived rape, torture, attacks, diseases, hunger and assassinations could only save their lives. Leaving behind all their lives in the Anatolian land, their homeland.

So this personal exhibition in DEPO also served the purpose of giving back the lost history to a nation. And if it were not for Khanjian I would not comprehend this truth in its full course. They could not have family albums dating back to their ancestors. Their albums were at pawn in this land that I call my country. They were destroyed and then everything was denied.

To comprehend it fully naming the Genocide was not enough. To understand the full catastrophe of the genocide, to understand its current impact on Armenians, their lost history, to understand our intertwined mutual past as two nations (or may be more if we think about the Kurds and the Circassians) as the victim and the perpetrator and to understand our future you had to comprehend that Genocide is an undeniable part of the Armenian identity.

Armen Marsoobian says this about the exhibition: “Many such families count themselves lucky to have a few photographs and orally conveyed stories that were snatched from the flames that marked the end of Armenian life on their historic homeland. Our family is privileged to have more, much more, that allows us to reconstruct what their lives were like in those historic lands. This exhibition marks the beginning of a continuing process in which I will discharge this moral obligation to tell the history of this Armenian family and more importantly, tell the story of the Armenian people during the momentous time in their history.”

Go and see the “Bearing Witness To The Lost History of An Armenian Family-Through The Lens of The Dildilian Brothers” exhibition. The curators are Kirkor Sahakoglu and Anna Turay. Turay also did the rewriting of the texts.

Go and see it because it mirrors the lost history of Armenian people… Go and see it because it is a family album of our mutual, painful and bloody past…