Reclaiming the memory of dictatorship in Chile (3): Villa Grimaldi

Interview by: Noémi Lévy-Aksu

Located in the suburbs of Santiago, Villa Grimaldi is a large estate which was known as Cuartel Terranova and used as a place of detention, torture, and execution during the first years of the dictatorship of Pinochet, between 1973 and 1978. Many buildings of the facility were demolished but the estate was turned into a site of memory called Villa Grimaldi Park for Peace (Parque por la Paz Villa Grimaldi) in 1997. In our interview with Francisca Inzunza Canales, a member of the educative team, and Soledad Castillo, a survivor of Villa Grimaldi and human rights lawyer, we discussed the transformation of the site, the challenges to truth and justice in Chile, and the importance of survivors’ testimonies.

Villa Grimaldi was one of the first sites of memory to be reclaimed. What were the main stages of this struggle for this recovery and its protagonists? What was the role of the state?

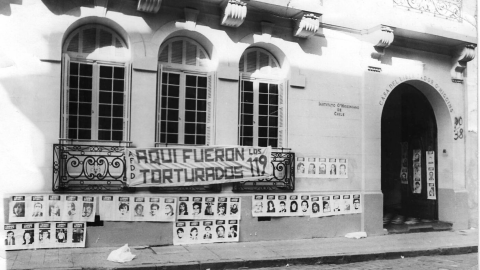

The recovery of Villa Grimaldi, that is its transformation into a site of memory, was part of a very long process, which started in the 1980s in Chile, when the repressive apparatus of the civil-military dictatorship began to be denounced forcefully and actively in the streets. A series of actions were carried out by human rights organizations and victims’ relatives to denounce the systematic violations of rights and enforced disappearances. In this context, public attention was drawn to the sites of repression. In the Peñalolén commune where Villa Grimaldi is located, local people and victims’ relatives started to gather outside of the villa, to make it visible that it had been used as a center of detention, torture, extermination, and enforced disappearance. They were the ones who finally managed to recover the site when the dictatorship was over. In the 1990s, the state expropriated the owner of the estate. Then, the whole process of dialogue began, to consider what to do with a place like this.

The state had an important role because reclaiming it would not have been possible without the process of transitional justice and the expropriation of the owners. Yet, the initiative belonged to the local communities and the civil society, which made it possible for Villa Grimaldi to be the first site to be reclaimed.

Before this recovery, most of the facilities of Villa Grimaldi were destroyed in an attempt to erase the history of this place. Thus, today the site is a beautiful park, which contrasts with the violence it witnessed in the early years of the dictatorship. How do you convey the past and honor the memory of the victims in this space?

We aim to recover the memory of all those people who passed through this place, but also to raise awareness about those who today are detained, disappeared, or executed. The memory of the site must allow us to work on the present.

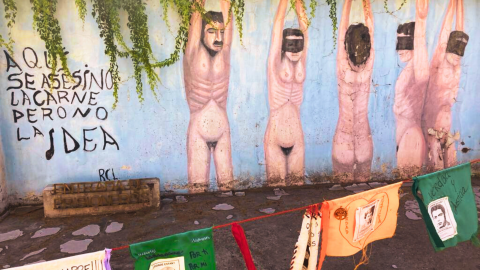

The site includes many symbolic elements. Due to the destruction of the facilities, we had to symbolically include all the memories related to the site and contribute to the recovery of justice and dignity. There are vestiges, inscriptions, and mosaics, which invite us to remember throughout Villa Grimaldi. The role of survivors has been tremendously important there because all those symbolic elements are based on the stories of these survivors, which enable us to convey this painful past. You have to remember that perpetrators do not talk, their pact of silence still protects them.

You organize numerous visits and workshops for children and young people. To what extent do they know about the dictatorship and are interested in knowing about it? How do you address gross human rights violations with a young public?

This is a complex question because over the years the knowledge of the repressive past was erased, and the truth was dissimulated. That has a lot to do with the state’s attempt to control the population, to prevent justice from advancing and truth from being known.

That is why it has been so important to create mechanisms to bring the different generations closer to knowing their history. We particularly work with children and youth, from kindergarten to university. Villa Grimaldi has developed a pedagogical model that combines the pedagogy of memory with education in human rights. We work around four axes: the link between the past and the present; the promotion of a culture of human rights; the involvement of local communities; and the development of a critical memory. In our pedagogical tours, we invite the participants to learn about the history of the site of memory, but above all to understand the struggles of that time and their relevance for the present. We want them to understand that these activists were targeted because they were fighting for a fairer society, rights, and justice.

Besides the youth, there are older generations who ignore what happened because the media was not free during the dictatorship. Enforced disappearances were never mentioned and the political prisoners were described as criminals and terrorists. Only the victims, their relatives, human rights organizations, and interested people knew what was happening. Therefore, there is an entire generation who lived unaware of events that occurred in this country and consequently did not transmit the information to their children, to the next generation.

This is why our memory work is so important, and why teachers seek sites of memory to address these issues. Unfortunately, this country still does not have a comprehensive memory policy. The history of the dictatorship and human rights have been incorporated into the curriculum, but this remains insufficient because human rights are still perceived as something ideological in Chile. Therefore, these themes can be overlooked when a teacher, a school director, or a municipality does not believe in their importance.

One of the aims of the dictatorship was to dismantle solidarities and collective initiatives, to establish an economic model based on individualism, where people would not be interested in their histories nor the experiences of others. Therefore, we need to invite the visitors to reflect on the present and their rights and issues, such as police violence or the rights violations experienced by the migrants.

Our local integration is also fundamental for us. We are in a neighborhood which is very active in social movements. Since the end of the pandemic, we have been making efforts to strengthen our relations with the collectives of the neighborhood, for instance for the celebration of Women’s Day on March 8, connecting with the women artists active in the neighborhood.

Soledad, you are a survivor of the Villa Grimaldi and a human rights lawyer. You are actively involved in the activities of the villa. Why is impunity still prevailing in Chile for the perpetrators of human rights violations during the dictatorship? Could you tell us about your struggle to have rape acknowledged by the law as a specific method of torture?

I think that the main obstacle to truth and justice has been the pact of silence among the perpetrators. To this day, there is no willingness to hand over information and only a limited number of perpetrators were convicted. In particular, while some military officers have been convicted, justice has not acknowledged the role of civilians in this perverse organization of destruction, rape, and death during the dictatorship. Impunity is almost total for these civilian perpetrators.

As for the recognition of rape as a method of torture, we have not made any progress in this country, and impunity continues to prevail in this respect. For the first time, in 2014, together with three other women survivors of torture, we brought a legal case where we asked that torture be recognized as a method of torture. This was an important turning point because it made these crimes visible and encouraged the victims to report them. At the same time, it was then also possible to prove that it was a systematic practice in the places of torture of detention, not an exception. All the women detained were sexually abused, but rape is still not recognized as a specific form of torture in law, and there is no public policy to guarantee the non-repetition of these crimes.

Soledad, I also wanted to ask what the personal meaning of your engagement with the Villa Grimaldi is and what is the message you convey when you share your experience with the visitors. Do you believe that sites of memory also contribute to the struggle for justice?

My contribution to the Villa Grimaldi has been to make events of the past more visible. I have been a political activist since a very young age but it took me a long time to make my personal experience as a survivor a part of this political commitment. With the case in 2014, I realized the importance of verbalizing our experience and transmitting it to the new generations. Indeed, if we do not speak, we contribute to the ongoing impunity in this country. The new generations must be aware of what happened, this is the condition for working on never again.

In the absence of strong public policy, the sites of memory are essential spaces for this transmission and the survivors’ testimonies make an important difference. Saying “this happened” is very different than saying “this happened to me”, the visitors are more impacted when they can learn about this history directly from a survivor.

I was arrested when I was 15 years old and I am already a senior citizen. The survivors of the dictatorship are fewer and fewer, as well as the perpetrators, most of whom have died in absolute impunity. This is why it is so important for me to testify now, to commit to the activities organized by the site.

In each visit that I guide, the main message that I convey is the importance of respecting one another and the importance of not accepting that harm be done to others. Unfortunately, in our country the neoliberal system that prevails promotes individualism and people can live in a deep indifference to the sufferings of others. I would like human beings to recover that sensitivity of putting themselves in the place of the other and not allowing the repetition of the terrible situations that many Chileans suffered, just because they were thinking differently.

*The original language of the conversation Noémi Lévy-Aksu had with Marta Cisterna Flores was Spanish. This text is the translated and edited version of the transcription.

**The image used at the beginning shows the memorial located in the front yard of Villa Grimaldi. The text reads “El olvido está lleno de memoria / Oblivion is full of memory.”