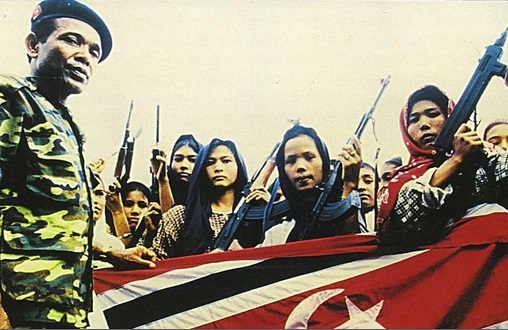

Free Aceh Movement (GAM) was established in 1976 and carried out an armed campaign against the government of Indonesia until 2005.

In order to have a better understanding of what was missing in Turkey’s peace process, one of the cases we wanted to look closer was Indonesia. In terms of the mechanisms employed in its peace process, we believe that Indonesian case provides important lessons for a future resolution of the conflict in Turkey. The interview we held with Marta Nogareda Morena focused on these issues, who was in Istanbul as the participant to our two-day closed workshop that took place as part of our project Defending Peace in Difficult Times. Morena was a member of the European Union’s Aceh Monitoring Mission operated for a year from 2005 to 2006.

How do you summarize the causes for the conflict in Indonesia?

The conflict in Aceh was based on a nostalgia from the past. Because at the beginning of the 17th century, Aceh was a sultanate, an independent state and it was the most powerful in the region. Then the power declined and they suffered the Dutch colonization. So they had a long history of war. First a 137 years fighting against a foreign power, the Dutch, and then the struggle for independence against the government of Indonesia, the army of Indonesia. The security forces were very strong in this region. They always had a very strong position in Aceh to stop the claim for independence. The Free Aceh Movement (GAM), the rebels group was a reaction to this strong presence and abuses of the Indonesian army. When the time went by, the GAM itself became also quite abusive too, so both sides committed human rights violations. And it was the civil society, the people of Aceh that was suffering from both sides. These are the roots. Like, ok, this nostalgia of the sultanate.

In your presentation you also mentioned about the natural resources and distribution of resources.

Of course, yes. This is a very important point. Aceh is very rich in natural resources. So the central government was taking these resources without any return to the province. So let’s say that the central administration was getting richer by using or selling these natural resources. Aceh was getting poorer and poorer. In 1976, Hasan di Tiro, who is descendent of the sultan’s dynasty, created the Free Aceh Movement because of the abuses, of what I’ve just said regarding the natural resources and this nostalgia…. Aceh was declared independent by this person and his group, the GAM.

By 1970s The Free Aceh Movement raised the struggle for independence. Despite military suppression, new waves of rebellions kept emerging for many times. At which stage did the military solution became longer an option for the government?

What happened after 30 years of conflict is that there’s been a political change; a new president who wants to do things differently. And this political will from the side of Indonesian government was essential. But there was also a change in the GAM side. The leadership also realizes that they are very tired of the conflict. And that maybe the claim of independence, they feel, is in an impasse.

And then there was this unforeseen event that is the tsunami. The ground was almost ready for the two sides, and the tsunami turned out to be the last drop of water. After the tsunami people of Aceh were put at the center of considerations. Before that people were not considered, but after the tsunami the province was so devastated that the two sides felt helping the people was the main priority.

More than 200 thousand people lost their lives after the tsunami that followed the earthquake of 9.1 magnitude in South Asia. Big part of the casualties took place in the Aceh region. This catastrophe is known to be influential for the start of the peace negotations.

What were some of the key issues in peace negotiations?

So, first of all I would say that the new mediator, the personality of the new mediator, used a different formula. One that is different from the traditional. This is essential. He didn’t start with ceasefire, but by talking about the fundamental political questions and issues. And the core issue was whether Aceh and the GAM wanted independence, or to remain within the state of Indonesia. And this was solved by GAM renouncing, abandoning, giving up on the independence and being happy, I would say, with having a special status within Indonesia.

Another issue was of course the signing of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) and the establishment of the Aceh Monitoring Mission (AMM). The monitoring mission was also very specific to the MoU, which has given a lot of importance to the monitoring activities of a third party. So the AMM and its mandate was concluded in 15 months. And then the third phase was the rest of the process is until today.

And how did peace impact on the distribution of resources and economic situation in Aceh?

Well, now the Aceh people, having direct local elections, have the power to elect their own governors, their own rulers, regional provincial rulers. And how are these rulers doing their job? Nowadays, we know that Aceh is not a developed province but is in the normal developing rhythm of the whole country. So maybe Aceh is a bit below average because it is still a remote province. Jakarta is doing differently. But it’s usually like this, it is a very unitary central state. So a lot of issues that were present during the conflict are still there. The issue of natural resources management and the problems of corruption. Like in any other part of the country.

Marta Nogareda Morena witnessed the damage caused by the tsunami during her duty as part of the AMM, which became operational after the signing of the MoU on 15 August 2005. The mission finalized it’s main work on December 2006, but remained active until 2012.

Can you give a little detail about the AMM and MoU? What was their scope and what were some of the key issues in their implementation?

The MoU has a wide range of provisions. And not all of them were part of the AMM mandate. So the AMM had to monitor several aspects of the MoU and these tasks were completed. These were demobilization, decommissioning, re-integration; withdrawal of the military and police forces; reintegration of active GAM members; the organization of the first direct local elections and; the human rights monitoring throughout the mission. If during those 15 months someone was coming to our offices saying: ‘This has happened to me’, we would investigate it and rule on it. But only in the framework of the MoU.

So the AMM mandate was completed, and then the MoU still needed to be implemented. And I want to emphasize that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was not implemented. And also the Human Rights Court is not yet in place. There are other provisions that were not put in place, but I will underline these because they are probably the ones most connected to our mandate. AMM’s human rights mandate was subject to debate also in the European Council. What should it monitor? The whole human rights abuses in Indonesia or only those in the framework of the MoU? So finally, the EU Council decided to have a narrow mandate on human rights, and this we did. But this broader issue of human rights abuses has not yet been solved.

Experts emphasize the importance of socializing peace processes. What do you think the role of civil society should be in achieving this?

In Aceh what I see is that there is a culture of submission. There is a long history of submission. There has always been someone telling the society what to do, what to think. So in a way, it is like a childish society. And they don’t ask for their rights. There has been no accountability on human rights abuses before the MoU. Thank God, there are certain documentaries like the Act of Killing. But it’s someone from abroad going there. Of course the protagonist is the brother of an assassinated person, where one of them wants to remain anonymous. And this is the culture. Most of those who are saying that there is no human rights accountability in Aceh are foreign organizations. Of course there are certain and powerful human rights organizations, but there is no critical mass. The mentality is to accept the suffering and not take action. They don’t have a critical mind that maybe we have in the western world. I could see this attitude also towards the tsunami, and towards natural disasters. You cannot blame anyone, ‘OK this is our fate.’ Of course there is an important human rights movement but it’s not enough. I think there is no culture like you have in Turkey or we have maybe in Spain.

Joshua Oppenheimer’s movie “The Act of Killing” focuses on the stories of perpetrators of the massacres towards the communist in 1965. In this photo, we see Anwar Congo, one of the perpetrators, looking at the camera during the shooting of the movie. Photo. Drafthouse Films / Everett.

And when I saw this documentary, the Act of Killing, I was really, my blood was burning, but I could see that. They were interviewing people that killed in the past. They were in power. They were in local authorities. And that’s it. At least the documentary shows the reality but the submission attitude is there…

You mentioned about the practice of Sharia Law in Aceh. How did this contradict with the mandate of the AMM?

So the Sharia Law was there and is there. And it’s the decision of the people of Aceh to keep this element. So as a foreign mission we wanted to respect the decisions of the people of Aceh. Therefore we didn’t ask or we didn’t touch this issue. It is true that the Sharia Law was and the Sharia police was active during the implementation of the first months of the MoU and during the AMM mission. But we tried to keep the Aceh mandate, and not question any other issue. So we tried to do the best we could. And now the issue is in the hands of the Acehnese people. Now the human rights organizations are asking for the abolishment of the Sharia. And yeah, after the AMM finished and concluded its mandate, now the issue of the Sharia law is, as it was before, in the hands of the society and decision makers. Of course there is this human rights pressure to abolish the Sharia. But, apparently it’s not yet enough.

Interview: Kerem Çiftçioğlu-Burcu Ballıktaş Bingöllü, Translation: Ceren Yartan