Government forces patrolling a deserted village in Pikit, south of the Philippines, stronghold of Muslim rebel group Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MNLF)\ during the peace talks between MNLF and Philippine govenment. Photo credit: GZO Peace Institute

The conflict in the Philippines is one of the most protracted in the world, but one that is also going through a long and innovative reconciliation process. Due to this, and its similarities in terms of ethnic nature and prolonged duration, comparisons have been made to the conflict in Turkey. It was for this reason that Kristian Herbolzheimer was one of the two experts we invited to a recent 2-days workshop we held as part of our project “Defending Peace in Difficult Times”. Herbolzheimer is the Director of the Transitions to Peace Programme in Conciliation Center, and is an expert that closely monitors the peace process in the Philippines. You may read his full bio at the bottom of the page.

What are the root causes and historical grievances about the conflicts in the Philippines?

KH: Well there are two armed conflicts in the Philippines. One is a communist insurgency all over the country, and then in the southern part of the country there is Muslim guerilla fighting for self-determination in a predominantly Catholic country. And both of these conflicts have been going on for more than 50 years now. The grievances are of course different. For the communist guerilla, it is essentially a matter of land distribution and access to political power for the marginalized sectors. And with a very strong Maoist ideology, the purpose is to overthrow a regime which they consider as sustaining power dynamics that are semi-feudal and actually controlled by the United States. It’s an anti-imperialist struggle.

In the South, the Muslim struggle is essentially for what they call “parity of esteem”. The objective is again to not being marginalized as they have been in the national Philippine history ever since it gained independence 60 years ago. So these are the root causes of both conflicts.

The conflicts in Philippines are among the most protracted in the world. What are the societal and structural reasons behind it?

It is indeed one of the most protracted conflicts in the world. There are few others which also have been going on for several decades. I think it is important to highlight that it is a low-intensity conflict, which are defined as conflicts where there are less than 100 deaths per year. So it had its highest armed confrontations during the years of dictatorship in the late 70s and in the early 80s. Over the last 30 years, these are conflicts with a less than a hundred people dead. So it’s not that as if people are suffering the intensity of the battle throughout 50 years. They suffer poor governance and weak state structure and continued marginalization of peoples. And the reason that they have not been able to sort things out previously is in part related to this state weakness and to a certain extent even insurgent weakness.

You need two things to terminate an armed conflict. You need political will and then you need the capacity of implementing that will. And I think there has been shifting political will in the different governments and also in the leadership of different armed groups. When there has been political will, then something has not been enough in terms of capacity to make change happen.

And so in the current negotiations, what led the actors to come to the table? What has been the impact of different factors like economy, civil society or leaders?

One of the factors leading to negotiations is of course that because the conflict is protracted, it is clear to both sides that nobody will win the war. So if nobody’s going to win the war, then you have to find a negotiated solution. And then the question comes: With what power do the parties have come to the table? What is a negotiating agenda? How much popular support do they have to endorse their own political agenda? This is all part of the conversations.

It is interesting that in the Philippines, civil society has been very active and quite creative. Some of the most innovative initiatives in the world have come from the Philippines. One of them is for instance civil society monitoring of the ceasefire. That is something now spreading to other contexts but originally this is something that came from Mindanao in the Philippines. Sometimes, civil society leaders have managed to become part of the government. The government has been quite flexible to appoint civil society leaders as chief negotiators on behalf of the government. So what I’m trying to say is that it is a context where creativity is enhanced. When there is creativity and leadership, there is possibility for civil society to play a significant role.

People in peace rallies in support of Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL) in Lanao del Sur on 2014. Photo credit: “Lanao del Sur in Focus“

Could you elaborate more as to what was innovative in negotiations? And usually in conflicts, the parties have different definitions about the problem. How was this issue addressed?

There’s one thing that makes peace processes easier in the Philippines. It is a fact that there is no discussion as to what the problem is, what the root causes are. I think one of the most interesting innovations in the Philippines is that between ’92 and ’93, there was a national consultation organized by the government asking the people, everybody in the Philippines, “What does peace mean to you and what do we have to do to get there?” And after that broad consultation, the country came up with a peace policy which they called the “Six Paths to Peace”. One path is the negotiations, but people also identified five additional paths to peace which are equally important. After that, the government decided to create an Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process: OPAPP.

Infographics produced by the OPAPP to inform the public about the “Six Paths to Peace” mechanism. The office also has a very up to date Facebook page.

That has been an office that has been carrying the mandate of that national consultation ever since it happened 25 years ago. So, despite different governments over these past 25 years, none of them has challenged the results of that consultation and that means none of them has challenged that there are root causes to the armed conflict that need to be addressed. That of course makes it easier. Then you don’t have disagreements on what the problem we want to address. There’s of course a disagreement on how we address it, but that made it easier.

And then in terms of how you address it. As I said, some innovations have been to create peace zones, which are demilitarized zones for civilians to live without suffering the consequences of the war. There have been massive demonstrations against internal displacement. There has been something they call the “backwit power”[1] which is the power of the displaced people. They have taken the road to protest their situation of displacement due to clashes, violent clashes between combatting factions.

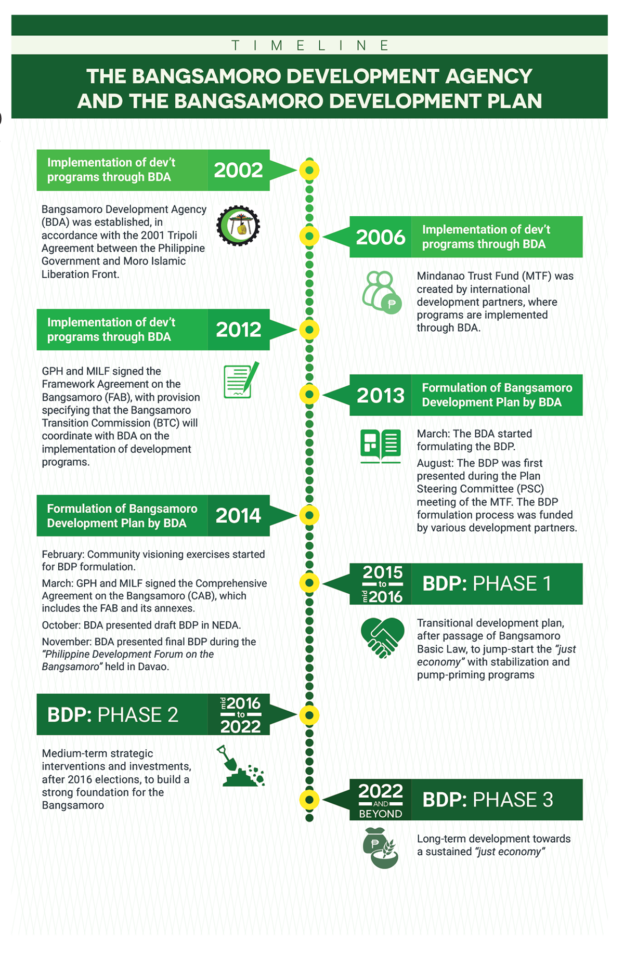

There has been this idea of a Bantay Ceasefire which is creating a ceasefire monitoring from civil society. The government has been open to allow the guerilla, once there was enough trust to create what they call the Bangsamoro Development Agency, which is essentially a development agency that receives international funds, but which is run by the insurgency with the government accepting that. Or they have created Bangsamoro Institute for Leadership and Management which is a capacity-building institute run by the insurgency to create a new civil servant leadership that will take responsibility after the signing of the peace agreement. The government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front have agreed to create an international contact group which is something that happens very often. But the innovation is that for the first time in the world in the contact group, there are not only countries but there are also international civil society organizations. I myself represent Conciliation Resources in that international contact group and that could go on and on.

Infographic produced by the National Economic and Development Authority of the Government of the Philippines.

I think it is also very important to highlight that because you cannot apply a recipe for peace. Every conflict where people try to solve a conflict ask similar questions and they try to learn from other processes and they get inspiration. But because you cannot copy paste from elsewhere, you need to do something different to adjust to your own context. Inevitably, always, therefore, any peace process there’s always something you have not done. So I think it’s very important or very interesting to highlight that any peace process learns from others. But at the same time contributes to others.

And what is the unique contribution of the Philippine case for other peace processes around the world?

Well I think if I need to highlight two or three would be the framework of the Six Paths to Peace: The National Consultation leading to the peace framework, the international peace framework that will be one of the big highlights. The other one will be a Ceasefire Monitoring and the third one would be creating this international support body which is composed of states but also of civil society organizations.

How do you see the correlation between democratization and peace negotiations? In the Philippines, did the democratic transition in 1986 have an impact on the resolution of the conflict?

Well. The Philippines had a dictatorship until 1986. A dictatorship that was defeated by a People’s Power Revolution. That is maybe also very interesting to highlight because it was a massive nonviolent street protest that eventually terminated the dictatorship and that has also been a source of inspiration for similar movements as well in the world.

After that, expectations for democratic change in the country were very high and I’m afraid this has not been met. Making change happen, and in this case I mean structural change, so that a government truly responds to the needs and rights of their citizenship in the Philippines, has proven to be a very slow process. However, in the Philippines and elsewhere, the peace process is seen and understood as a fundamental component of democratization processes. So it is acknowledged that there is a democratic deficit which has led to the conflict in the first place. And what you need for the consolidation of the democracy is to find a peaceful way of settling the conflicts, the two conflicts in the case of Philippines.

Coming to today, now Philippines has a new president, Rodrigo Duterte. And in the context of this rising populism around the world, the Philippines seems to be one of the cases that confirm this trend. So what do you see as the prospects of the future of the peace agreement?

Well as in many other places. This kind of political leadership is extremely unpredictable. And what is being said one day might be different from what is being done the day after. For now, it is important to highlight that President Duterte has shown a very strong commitment to putting a peaceful end to both armed conflicts. So he has taken some bold steps in that direction, even bolder than any president before. So shortly after coming into office he appointed three members, politically close to the communist insurgency as members of his cabinet so they became ministers. And that was something nobody had done before. It was a very serious and important confidence building measure which immediately therefore led to the resumption of negotiations. For one year there were very fruitful negotiations that were proceeding at the speed that had not been observed for the last 20 years. And then they fell off.

Fell off when?

More or less in June 2017. They were supposed to have a new round of negotiations and that never happened until today, May 2018. So one year has passed without talks, but now there are indications that they may resume again. As I said, there is a level of unpredictability, of uncertainty. What happens in these kinds of regimes is that when a president has political will, he can make things happen very quickly towards negotiations. He can also go the other direction very quickly. But for both peace processes, it looks like over the coming weeks there will be very significant and positive developments. This of course is very paradoxical because on the other hand, in terms of good governance, rule of law and respect for human rights, the Philippines is going through very difficult times right now.

So that paradox is very similar in Turkey. That was the reason why I asked about the correlation between negotiations and democratization. From that perspective, as an outside observer, what would be your recommendations for a prospect of peace in Turkey? Maybe drawing on this notion of “unexpected things happen at unexpected times” that you mentioned in your presentation.

That’s because unexpected things happen at expected times, which we sometimes technically call “windows of opportunity”. You need two things, you need to have the capacity to detect when a window of opportunity approaches. Because it’s not always evident before it opens. And that means you need to be ready to see beyond the obvious. That’s one thing. Because maybe if you don’t see beyond the obvious and by the time you realize, maybe the window is already closing. And the second thing is, you need to know what needs to be done. And most often, especially in relation to peace processes, it’s not immediately clear what needs to be done in terms of the sequencing, who needs to do what, what are that technical, institutional, political steps that need to be taken. And therefore I think, even in the absence of prospects of negotiations, it is a task of civil society, of academics, of politicians, of any kind of social, political and even economic leaders to be preparing themselves, doing their homework. So whenever this opportunity opens up you’re ready to respond.

[1] “Bakwit” is a local word for “evacuee” or “displaced person”. So it refers to a movement of displaced people.

Interview: Kerem Çiftçioğlu, Translation: Ceren Yartan

Kristian Herbolzheimer

Since 2009, Kristian Herbolzheimer has been working as the Transition to Peace Programme Director in Conciliation Resources (www.c-r.org), a London based international NGO that supports people in the field of conflict resolution. Herbolzheimer monitors the peace negotiations in the Philippines and gives consultation to both the Philippines government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) as part of his mission to represent the Conciliation Resources at the International Contact Group on Mindanao.

Herbolzheimer has also been supporting the peace initiatives in Colombia since 2000, where he mainly works on the political discrepancies between the grassroots groups and the decision-makers. Previously he worked for seven years as Program Director of the School for a Culture of Peace, Autonomous University of Barcelona, supporting peace processes and conducting track-two diplomacy in Colombia, Philippines, Western Sahara, Basque Country and elsewhere.

Kristian earned a Masters degree in International Peacebuilding from the Kroc Institute, University of Notre Dame, in May 2009. He also holds a degree in Agriculture Engineering and a Diploma in Peace Culture. He has long been active in Catalan grassroots environmental and development organisations.