The Responsibility to Remember: Memory Activism and Dialogue in Armenia

Interview: Noémi Lévy-Aksu

Memory studies and memory activism are at the core of the CSN lab activities and mission. How would you define your contribution to this field, and how does your approach differ from the prevailing discourse and methods in Armenia?

Tigran Amiryan: In the context of Armenia and the wider region, with all the shifts, empires, wars, conflicts, and waves of migration, we’re dealing with a multilayered and what we often call a complex past. One of the few ways to navigate these layers without getting trapped in official discourses or rewritten histories is through memory studies. It allows us to decentralise narratives, turn history into histories, identity into identities, and open up space for multiple voices and perspectives.

I believe our work has genuinely shifted the atmosphere around memory discourse in Armenia, and I can highlight a few key points. First and foremost, we’ve done something that academia has long avoided, something often promised in the forewords of academic texts but rarely realised. We adopted an interdisciplinary approach, bringing together anthropology, sociology, urban studies, literary theory, philosophy, and even artistic practices to speak about memory and the past.

Beyond methodology, our mission has always been to analyse and amplify the life stories of ordinary people. Political discourse is often full of exclusion, conflict, and the struggle for power. In contrast, the memory of ordinary people speaks more honestly about lived reality. In this sense, we constantly strive for a more democratic politics of memory. Knowledge about the past shouldn’t be locked away in academic institutions, archives, or closed circles, it must be accessible to those whose past it is and belong to the public. This is what we mean by the fight for democratic memory.

Arsen Abrahamyan: With the team at CSN Lab, we’ve also been working to bring attention to communities and experiences that have long been silenced, not only in Armenia but across the region. While memory studies in Armenia have mostly focused on the Genocide, particularly survivor testimonies and post-memory narratives, which are undeniably crucial, other narratives have remained in the shadow. At CSN Lab, we aim to broaden the field by exploring cultural and social memory through perspectives of urbanism and architecture, natural landscape and environmental transformations, displacement and ecomigration, gender and queerness. These perspectives help us engage with the past in its full complexity.

If memory shapes identity, then acknowledging the diversity of memory means embracing diverse identities too. Remembering, for us, is also a right—a right to exist, to have a transparent past, and to imagine a future.

The Armenian Genocide holds a central place in national historiography and collective memory in Armenia. Has the state narrative on the genocide changed over the decades? And do you see alternative narratives emerging in academia or civil society?

Tigran Amiryan: State narratives around the Genocide have changed significantly, not only during major political shifts, like the Sovietization of Armenia and the collapse of the Union, but also across different regimes and leadership changes in Armenia. If we look closely, we can see how the politics of memory have gone through several phases: from periods of restriction and silence, such as the early Soviet era, when public discourse and institutional recognition of the Genocide were practically nonexistent, to later periods, particularly in the 1960s, when the trauma of the Genocide was actively revived and instrumentalized, this time by Soviet authorities themselves, as part of pushing the idea of a national identity to position Armenia within broader regional power dynamics.

However, the official politics can shift or repress this memory, but this is not a narrative that can be easily altered, even amid new political agendas or diplomatic strategies. The Armenian Genocide remains a powerful narrative of memory and post-memory in Armenian society, especially because it continues to be politically instrumentalised and denied. As long as denial exists, the memory of the Genocide will remain a form of social and cultural resistance.

It’s evident that, in recent years, the Armenian government has tried to revise the politics of Genocide memory, aiming to take it out of the sphere of regional conflict. But, as with many things in our region, this process has been rushed, careless, and lacking proper dialogue with expert communities.

It is impossible to shape an “alternative narrative” when the Genocide is a historical fact. Each of our family histories is, in some way, tied to 1915. So the question isn’t about alternatives, it’s about responsibility. The Genocide should no longer be used as a political instrument or as an excuse for diplomatic silence. It deserves to be addressed with dignity, not manipulated for power.

The recent comments of Prime Minister Pashinyan

Arsen Abrahamyan: Over the past 30 years of Armenia’s independence, the state narrative around the Genocide has again shifted significantly, especially in connection with the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. After two wars and repeated escalations, these two traumatic events seem to have become intertwined in public discourse, adding further complexity to the dialogue between countries and societies.

In this context of post-war trauma and ongoing negotiations between Armenia and Azerbaijan, the Prime Minister’s recent statements unsurprisingly triggered intense public debate, particularly because this new wave of normalisation is unfolding without transparent communication. At the same time, the Turkish official discourse continues to rely on denial, making genuine dialogue even more difficult. For many in Armenian society, civil society organisations, academia, and broader communities, it remains unclear what the actual starting point of this normalisation process is.

With the current approach, maybe it is possible to imagine the land border reopening for goods or third-country citizens; however, dialogue between societies and between people requires a much deeper process, and this process must start with cultural dialogue and shared reflection on our complex past, not political bargaining alone. And the relationship between the two societies cannot be built on the erasure of trauma. No meaningful dialogue can begin from a place of denial.

That’s why, even as official diplomacy remains limited, independent cultural spaces and civil society actors continue to work toward dialogue, creating ways to reflect, connect, and build trust. It is not easy, especially after the Second Karabakh War and Turkey’s growing role in the region, but a few initiatives, including CSN Lab, remain committed to keeping that space for conversation alive.

You have been collaborating with historians, such as Hourig Attarian, to develop original methods to explore the spatial dimensions of the displacement and destruction in the aftermath of the Genocide. Could you tell us more about these research projects and methods, such as memory walks? Especially around traumatic pasts, there's often a tension between documentation and emotion, or fact and affect. How do you navigate this in your practice?

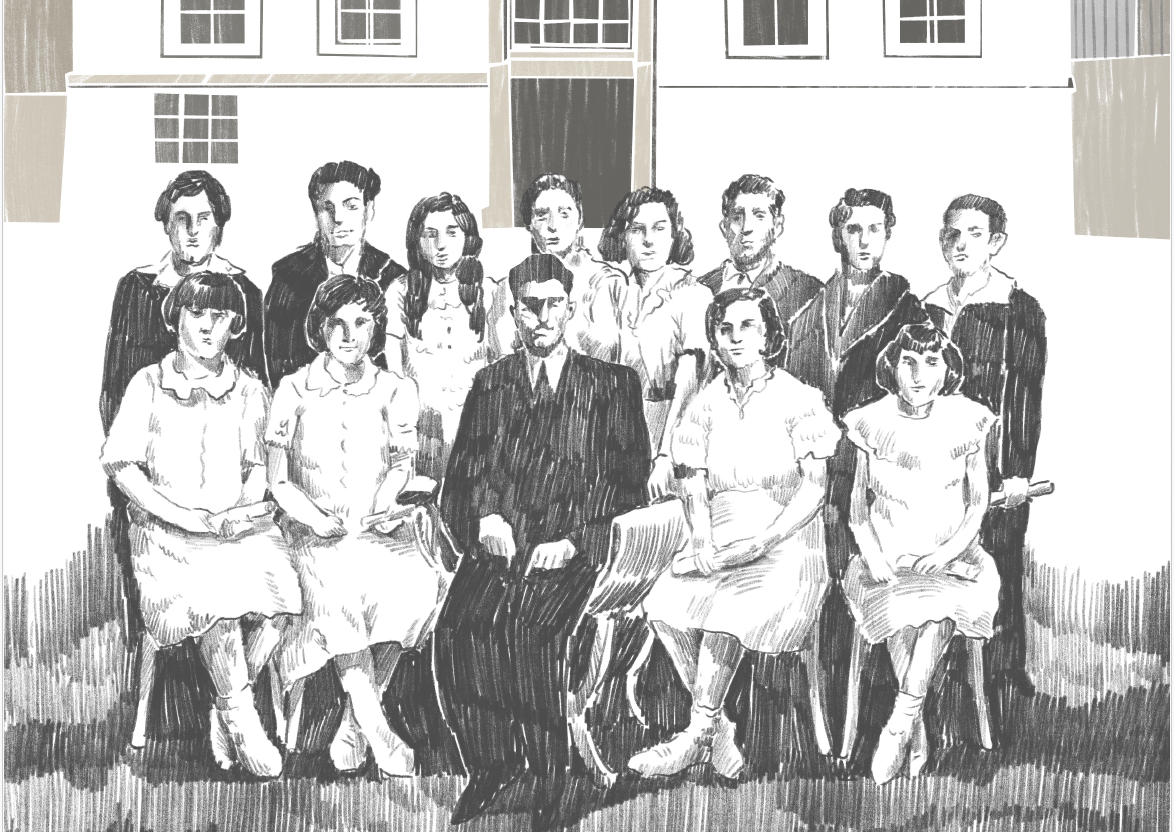

Tigran Amiryan: CSN Lab works across various formats: research publications, dialogue programs, conferences, mobility and exchange initiatives, art labs, exhibitions, podcasts, etc., but one of our most impactful initiatives is our alternative education program, the annual School of Complex Past. It was through this program that we collaborated with Dr. Hourig Attarian on the memory walk "From Sebastia to Sebastia: Tracing Genocide Memories", which explored the urban landscape of Malatia-Sebastia in Yerevan.

The walk traced the migration route of Armenians displaced from Sebastia during the Genocide who later settled in Soviet Armenia. Drawing on years of oral history research and archival work, the project unpacked how layers of trauma, memory, and survival are embedded in the built environment: kindergartens, factories, houses, and parks, all telling stories of loss, migration, and resilience. Each stop was a site of layered memory.

I was born and raised in that neighbourhood, and the walk deeply resonated with me. We had always known fragments of each other’s past, Soviet memories, the trauma of Baku refugees, repatriant neighbours from Lebanon and Greece, the shared hardship of the 1990s, but the walk revealed how much remains unspoken. The silence around 1915 often comes from a sense that "everyone has the same story," or that nothing new can be said. But that silence itself is part of the trauma, a wound passed down through generations.

Projects like this show the importance of site-based research methods in memory work. The spatial reading of the district, combined with oral history and archival study, allowed us to approach memory not as a static fact but as something embedded in landscape and everyday life.

Are there new alliances or solidarities forming across borders—such as Turkish, Kurdish, or international memory activists—that influence your work or the broader field in Armenia? Do you observe a generational shift, with the younger generations inventing new tools or languages (art, digital media, etc.) in memory activism, to counter hate speech, nationalism and attacks against democracy?

Arsen Abrahamyan: Over the past seven years of working across the region, one thing has become very clear: on both sides of the border, there are people who genuinely want to get to know each other. In this context, memory is not only a source of division or conflict, but it can also become a point of connection. These emerging networks are often shaped by a younger generation that seeks to engage with the past in new ways, using interdisciplinary art, media, storytelling, and oral history, not only to rethink historical narratives but also to resist nationalism, hate speech, and authoritarianism.

In our work, we also try to reflect this shift. The digitisation of memory has become one of our key priorities. It allows us not only to preserve fragile materials and stories but to make them accessible across borders, reaching new audiences and bridging generations, as memory activism is not only about looking back, it’s about shaping what comes next.

Tigran Amiryan: This generational shift is clear. There is a growing demand for more open societies, for spaces of cultural dialogue, and for opportunities to learn from one another. Young Armenians want to move beyond the weight of unresolved histories and the stagnation of the post-Soviet transition. Turkish youth, too, are searching for ways to critically engage with inherited narratives and reimagine their place in the region.

Even in the absence of formal diplomatic relations, meaningful cultural collaborations have taken place. Culture has proven to be the most resilient and adaptable platform for connection. While political and economic channels often remain closed or ineffective, culture continues to create space for sustained dialogue, exchange, and understanding. After decades of conflict and silence, we must ask: what is our alternative, if not responsibility and dialogue?

And today, during the days of commemoration of the past catastrophe, we, as a cultural organization, are involved in memory activism first and foremost through dialogue. Ahead of April 24, Arsen will host a delegation of civil society activists and researchers — Turks, Kurds, and Armenians — in Yerevan, while I will take part in a cultural dialogue in Berlin with a writer of Turkish background.

Today, we all share the understanding that there is no real alternative to open dialogue about our shared complex past.