The first hearing in the case of Diyarbakır Bar Association President Tahir Elçi, who had been killed in Diyarbakır on November 28, 2015, took place on October 21, 2020. Gülistan Zeren from Hafıza Merkezi wrote down her impressions from a Diyarbakır Courthouse under police siege.

Tahir Elçi was shot in the head on November 28, 2015 in Diyarbakır’s Sur district while reading a press release in front of the Four-Legged Minaret to draw attention to the damaging impact of armed conflict on cultural heritage. In the indictment, which was completed only 5 years after Elçi’s killing, on 20 March 2020, police officers Sinan Tabur, Mesut Sevgi and Fuat Tan, who were present on the street where the shooting took place, were charged with “causing death by culpable negligence,” while it was considered that PKK member Uğur Yakışır had committed the crime of “causing death through recklessness.” The first hearing of the case was held at Diyarbakır 10th High Criminal Court on October 21, 2020.

That morning, the entrance to the Diyarbakır Courthouse was surrounded by police barriers and there were many water cannons, armored cars, busses filled with riot police around the courthouse. The long “border” drawn through the barriers created the impression that the courthouse was impenetrable. When we proceeded towards what we deemed to be the entrance, we were warned by the police: We could not pass right through the police, but had to walk along a second “border” drawn by security vehicles arranged in a semicircle. After passing two security checkpoints witg X-Ray devices and a general identity check, we were finally able to enter the courthouse.

A crowded group of plainclothes police waiting in front of a courtroom made us guess that this was where first hearing of the Tahir Elçi case would be held. There was an information letter attached to both sides of the door stating that the room’s capacity was limited to 84 people due to the Covid-19 measures. All benches in the corridor were filled with riot police and plainclothes officers, apparently on duty for the Elçi case and numbering at least 70-80 in total. In other words, at least as many police officers as the number of people who would be in the courtroom had been deployed today, an exceptional state of security that radically disrupted the banality of a routine day at court.

But what exactly was it that made today’s hearing such a big security issue?

When the chief of police came out of the courtroom, which had not yet opened its doors for the hearing, followed by a group of security guards behind him, all of the police officers waiting in the long corridor rose to their feet and saluted him. Immediately after this, approximately 15-20 police officers with their shields, truncheons and helmets crossed the corridor in double file and entered the courtroom. All these intense security measures and crowded police presence created an uneasy atmosphere around and inside the courthouse. Obviously, the issue of accessibility of courthouses, where trials that are open to the public are held, cannot be reduced only to the availability of appropriate physical/spatial conditions (which were in fact not fully met at the Diyarbakır Courthouse that day): today’s situation, which would lead one to rather perceive the hearing as a security threat, made it almost impossible to achieve psycho-social conditions in which the audience and parties would feel safe and free from any kind of pressure

Entering the courtroom through the police corridor

We learned that the names of the attorneys of the complainants who would be admitted to the courtroom and of all the representatives of civil society organizations, parliamentarians and journalists who had come to observe and/or monitor the hearing had previously been notified to the prosecutor’s office by the bar association. There was a large group of bar association presidents, lawyers, journalists, civil society representatives, young trainee lawyers, and law students in front of the courtroom, but only those whose names were on the list would be allowed in. Undoubtedly, many people in this crowd had fought for human rights together with Tahir Elçi for years. Today, his colleagues and friends had come together to demand a fair trial in the case of the homicide of Elçi.

At the door, a bailiff and a police officer started calling those on the list one by one and let them in. In the corridor between the large entrance door and the courtroom, the police were aligned in cordons on each side. Waiting for my name to be called to be taken in to follow the trial was another ‘border-crossing’ experience during this day, and since I was not wearing a lawyer robe, I had to show my identity card again. After our identities were verified, the corridor was opened and we passed the corridor under the gaze of the police.

Members of parliament, representatives of civil society organizations and journalists took seat in the rows reserved for the audience in the courtroom. The chairs at the rear, however, were occupied by police officers only. The two plainclothes police officers next to the bench where the three prosecutors (the crowdedness of the prosecution, which constituted another exceptionality, had been justified by the “importance” of the case) appointed to the hearing had taken seat as well as the three plainclothes officers to the right of the clerk and the bailiff sat facing the audience during the entire hearing. The entire hearing was under surveillance: Watching the panel of judges and the parties, we ourselves were also being watched.

Anonymous defendants

None of the accused police officers were present at the hearing. They participated from Elazig, Malatya and Hatay via the audio-visual informatics system SEGBIS. The screen hanging on the wall behind the panel of judges was rather small. Even from the front row of the audience it was not possible to recognize the faces on the screen. Therefore, neither the complainant party nor us, the spectators, could perceive the presence of the defendants as something real. During this first hearing of the Tahir Elçi case, the defendants continued to remain somewhat anonymous for everyone in the courtroom. Neither the complainant party, the prosecution, or the panel of judges nor us as the audience were able to see the faces, gestures and attitudes of the people whose voices were only heard for a short time (SEGBIS connection could not be established due to technical problems for a long period of the hearing). But what were the compelling circumstances due to which the accused police officers were not with us at the hearing that day? Indeed, this question was not addressed to them. The presiding judge only asked them whether they would prefer to come to Diyarbakır for the hearings or to connect via SEGBIS from their respective locations. At the beginning of the hearing, the prosecutor summarized the indictment at the request of the presiding judge. Honestly speaking, his statements did not make it clear to those present at the hearing exactly what the defendants were charged with. Following the reading of the indictment, the presiding judge stated that they would commence with the defense of the defendants and that he wanted their defense to be taken without interruption. The attorneys of the complainant objected to this decision, stating that their requests to participate in the proceedings had to be taken before moving on to the defense, because they wanted to use their right to direct questions to the defendants during their defense, however the presiding judge did not accept these objections. It would later be understood that there were no delegated judges in any of the courtrooms from which the defendants were connected. While the absence of a judge responsible for verifying the identity of the defendants led to serious questioning and objections from the complainant party with respect to how to proceed with the trial, the prosecution did not get involved in this matter at all and kept its silence, which it would maintain throughout the hearing. The presiding judge, convinced that this situation did not matter much, decided to commence the hearing.

Türkan Elçi not allowed to speak

During the hearing, all other requests made by the complainant’s representatives were also denied by the presiding judge (who took all requests alone, without even considering consulting the other two members of the panel). Following this, the attorneys of the complainant declared that they would not be “a part of, an extra to the lawlessness practiced here,” and demanded a break from the presiding judge. They added that they needed to discuss how to position themselves in the face of the panel’s approach, which they considered unfair.

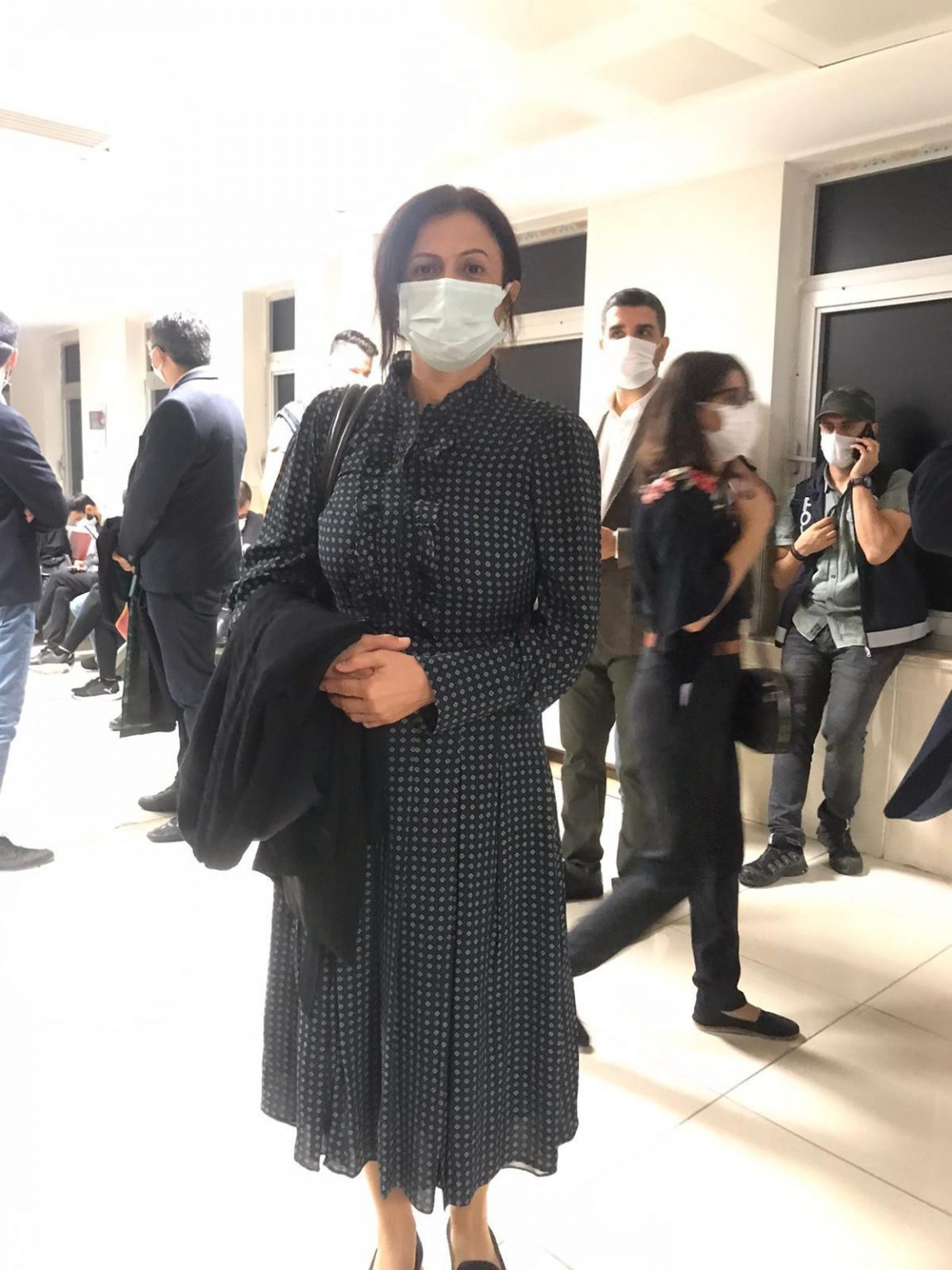

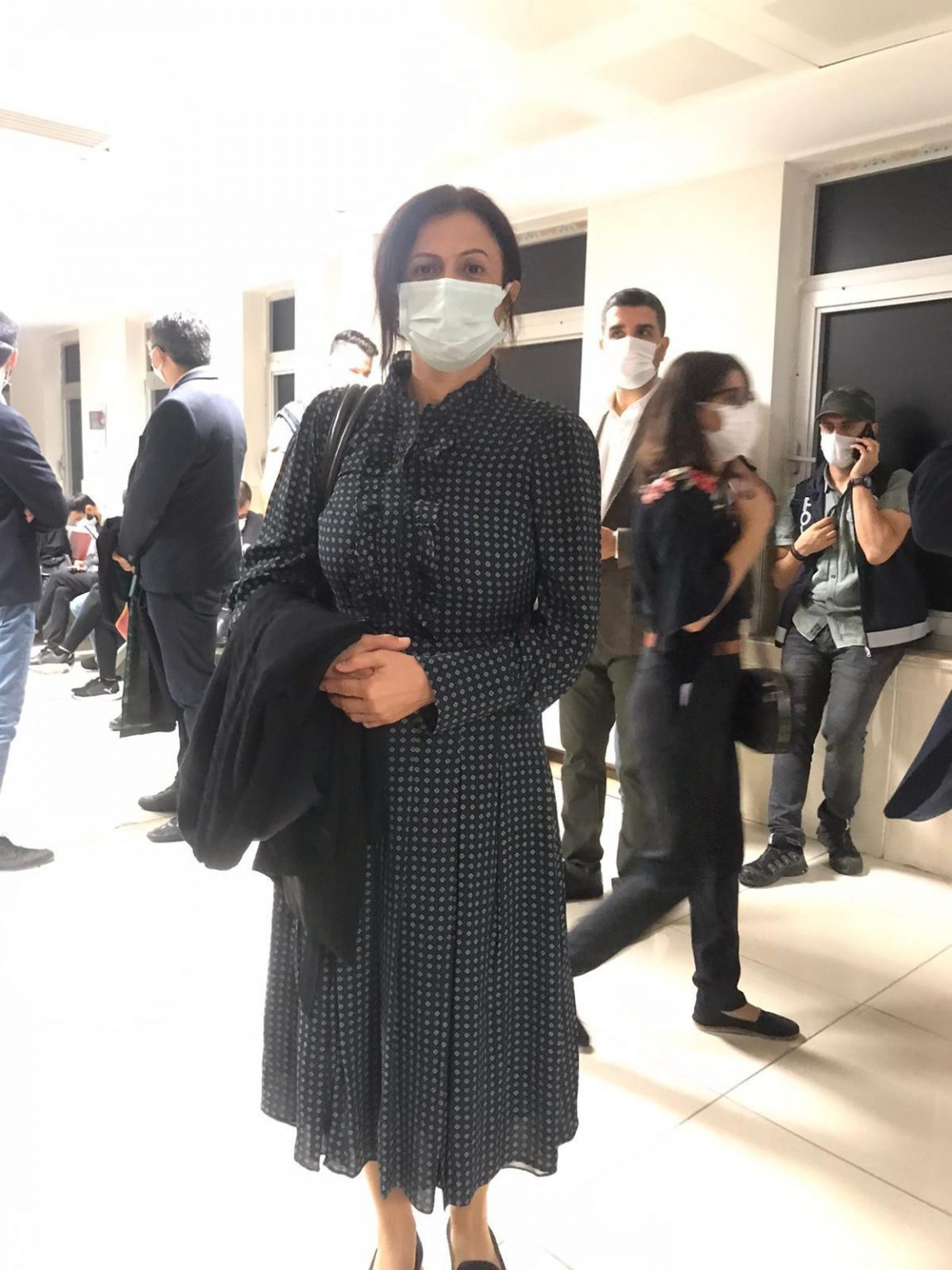

Türkan Elçi takes part as the law apprentice in the trial for the killing of her husband. Photo: Deniz Tekin

When we returned to the courtroom after the break, we saw that about 10 riot police were ready in front of the door where the panel of judges entered. It was noteworthy that the number of security guards in the courtroom had been increased. In the afternoon session of the hearing, Tahir Elçi’s wife Türkan Elçi took the floor. When Elçi started speaking, saying “I had full confidence in you until I got here”, she was hastily interrupted by the presiding judge. The panel did not allow Elçi to read the petition she had prepared and decided that Elçi be warned and would otherwise be removed from the courtroom. The presiding judge’s attitude towards Türkan Elçi further increased the tension in the room and made it impossible for the hearing to be continued. One of the lawyers of the complainant, attorney Nahit Eren asked, “You did not allow a person who lost her husband to speak for 2 minutes. Based on conscience will you make your decision?”

Complainants ignored during hearing

The panel of judges ignored the complainant party throughout the entire hearing. It clearly did not admit them to express their demands and opinions. Therefore, the lawyers of the complainants demanded recusal of the judge on the grounds that the panel was not acting independently and impartially. However, the panel ignored the request and threatened to remove the lawyers from the courtroom. When the objections continued, the panel listened to the demands and retreated to negotiate. Deciding to appeal to the next higher court to examine the demand for recusal, the panel ruled that the next hearing would be held on March 3, 2021.

After the hearing, the Elçi family and their lawyers made a press statement in front of the courthouse. Diyarbakır Bar Association President Cihan Aydın said, “It is obvious that the court has lost its impartiality. We can no longer expect a fair trial from this court. This is a trial built on spoliated evidence. They want to close the matter and they call this a trial. There is no trial here, technically there isn’t even a court.” Now, only outside the courthouse in which the case was held, Türkan Elçi had the opportunity to share her petition, which she had not been allowed to read during the hearing, with the members of the press and those who had come to observe the hearing. The first hearing of the case regarding the death of Tahir Elçi, who devoted his entire life to advocacy for people who were subjected to serious human rights violations, was carried out in a manner that raised concerns regarding a fair and effective trial.