Embroidery as a political tool: The empowering role of arpilleras for Chilean women

Interview by: Noémi Lévy-Aksu

Memorarte is a Chilean collective composed of women embroiderers [arpilleristas] who use traditional “arpillera” [embroidery] techniques to defend human rights. We had the chance to meet them during our field visit to the Chilean capital Santiago in January 2024. The arpilleras are a creative way of contributing to the demand for justice and to the struggle against different forms of violence and inequality in private and public spaces. In our interview with Erika Silva, the director of Memorarte, we discussed the role and significance of the arpilleras in the areas of collective memory and social activism in Chile.*

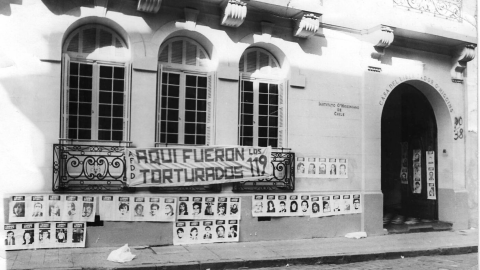

During our field visit, we had the opportunity to participate in a series of events organized on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights (MMDH) in Santiago. The arpilleras seen in the photo above were on display as part of the workshop organized by the Memorarte Collective for the 10th anniversary of the MMDH, which we also participated in. The arpillera with flowers in the middle reads “Floreciendo en la lucha,” which can be translated as “Flourishing/blossoming in struggle.”

The arpilleras became popular during the dictatorship of Pinochet. What was the meaning of this movement in those years?

During the dictatorship in Chile, the press was censored and the media were silent about the widespread human rights violations, the enforced disappearances, torture, and killings. Therefore, people looked for different ways to tell what was happening in Chile and one of those ways for women was to embroider using fabrics that were in the house. The Arpilleras network was a clandestine channel. It included women strongly committed to political activism and relatives of direct victims, but there was also another group of women who were very vulnerable economically, who sold the pieces to earn a living. They were the economic victims of the dictatorship, and in this sense their participation was also political. The movement was supported by an international network that allowed them to sell their products.

Your collective is called Memorarte. How do the arpilleras contribute to the memory of the dictatorship today and to the struggle for justice? Could we say that the arpilleras contribute to restorative justice?

An arpillera is a piece of historiographical truth that allows us to see and to understand. This is an image that in general moves people, because of its tenderness or its violence.

In Chile, history used to be taught like a timeline with events, heroes, and winners. Of course, the story was always told by the winner. On the other hand, memory is most often overlooked by this official history. Arpilleras are historiographical artifacts that allow us to break that chronological line and approach history and memory from other sensibilities, the sensibilities of those who are usually less listened to, of the subaltern, or the defeated.

Beyond the artistic product, the collective work which makes the arpilleras possible is also very significant, because memory has a greater resonance when it is part of a collective process. Women came together and created networks of conversations and production, which helped them face a hostile moment in history, making them feel that they were not alone.

I would like to refer to Axel Honneth’s three spheres of recognition [the private sphere, the legal sphere and the sphere of solidarity]. The legal sphere should acknowledge and uphold the rights of the individuals. Unfortunately, when we have a captured justice system, like in Chile, this is not the case. However, we have alternatives, we can turn to other spheres of recognition.

Let me give you an example. In the collections of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights (MMDH), there is an arpillera representing the killing of Rodrigo Rojas, a photographer who was burnt when he was 19 years old by the security forces in 1986. On the 30th anniversary of his murder, this was the first arpillera we took to the streets. There was a demonstration, which was attended by his mother, Veronica Negri. We ran towards Veronica Negri, his mother, and we gave her this arpillera. I told her, “We are giving you this arpillera, but I wish that we could give you justice because that is the only thing that matters.” I'll never forget her reply. She said, “The arpillera is also a way of doing justice.”

One can presume that the only thing that matters is the law, the decisions of the courts. But in reality, justice is also much more than that. Reparation, non-forgetting, memory, non-repetition, acting against denial. There are many other spheres of justice. In that sense, the role of the arpilleras in the dictatorship was very important and it remains significant today, in a democracy that continues to witness human rights violations.

My third question is about the present. How do the arpilleras relate to the current problems of Chile and what are your main areas of activism in the present? What are the relations of your network with the women’s movement?

The issues we are addressing are not specific to Chile. The limits of democracy and the consequences of neoliberalism and extractivism are all threats to the sustainability of this world. So how can we use art as a weapon of peace, a peace that is the daughter of justice? I see art as a way to channel the violence which sometimes overwhelms us against the system.

The arpilleras are a political channel of expression for women. This generates a lot of satisfaction because we are all together and we can talk, we can see each other, we can create together and we have this feeling that we are doing something. It's somehow psychomagical, I would end up with depression if I didn't have this space, which is a space of political activism but also of joy and happiness.

Regarding the relationship with the women’s movement, embroidery is traditionally considered an activity for women, but for us, it is a form of activism for women. We participate in the March 8th Coordination, which is the most important women’s coordination in Chile. We have also collaborated with the coordination of December 19th against femicides, and we work together with trade unions, feminist organizations, feminist artists, universities, women in prison...

For instance, this year we will organize a workshop with caregivers. A caregiver is a person who hardly leaves her home because she always has to be with a sick person who is usually bedridden or who is highly dependent. We went to find them at home, to reach even those women, as the most excluded of the excluded, with a minimum margin of freedom of action. These are the spaces in which we need to reach out, this is part of our political action. We are so interested not only in collaborating with women but also in knowing and impregnating ourselves with their realities, and their experiences. We need to be present in the private sphere, the houses of these poor caregivers.

As for the public sphere, we are making arpilleras for organizations, such as the Coordinadora Unitaria de Trabajadores (Workers’ United Coordination), which is a major organization of workers in Chile, and for other organizations as well. This is embroidery for the streets, but these works are also disseminated through social networks, and they can reach a broader public, beyond Chile. We are now in contact with many activists from different countries, discussing the ways of using embroidery as a political tool.

You have started talking about workshops and I know that you organize a lot of workshops. What are the different audiences and objectives of these workshops?

We organize a wide range of workshops, with different audiences. For instance, we work in prisons, with women “imprisoned for poverty,” as we say here in Chile. Most of them are there for micro-trafficking or petty theft, due to their poverty. We teach them the craft as an artistic expression, but also as a form of economic activity, and this is also something political.

We also do workshops in schools. We teach the technique to the children and we work with the teachers, to encourage them to use the arpilleras as a historiographical medium, and for many other purposes, as a means of expression. You may think that embroidery is for the old ones, but there is a lot of interest among young people and students.

The arpilleras can also be used as a form of storytelling for human rights organizations, throughout Chile and abroad. We do classes via Zoom, with women’s organizations, with victims of human rights violations, and with relatives of victims of femicide.

Could you share with us two arpilleras of your choice?

What you see above is the figure of a devil. In Chile, there was a lot of Chinese migration, so it's like a mixture between devil and dragon, which is like the bad guy of everything, right? It is shining, with a lot of glitter, and we call it “selfish.” Below, the hands that you see are symbols of the intelligence apparatus that imprisoned and killed people during the dictatorship. They refer to physical violence, exile, torture, and disappearance, but also to the whole system of extractivism, the neoliberal system. So here, the gloves are trapping water from the mountains, symbolizing the violence that continues after the dictatorship. Chile is not a poor country. Chile is an unequal country and that is not the same. Remember that Sebastián Piñera, the former president of Chile who died recently, was one of the richest men in the world.

The second arpillera is related to the memory of the dictatorship. This is the first arpillera I made, around 2011-2012. It represents a park called André Jarlán, close to where I live in Santiago. André Jarlán was a French priest, a defender of human rights, who was killed by the security forces during the protests of 1984. In that neighborhood, there was a kind of garbage dump, which was then turned into a beautiful park, named after him. I often think of the fate of this man, who was born in France and ended up being a park in Santiago. His family came to Santiago, and they found the park, instead of the loved one. This park is a form of reparation, a green space in a neighborhood that has few of them, a safe and peaceful area. This is what I wanted to convey with this green embroidery.

*The original language of the conversation Noémi Lévy-Aksu had with Erika Silva was Spanish. This text is the translated and edited version of the transcription.