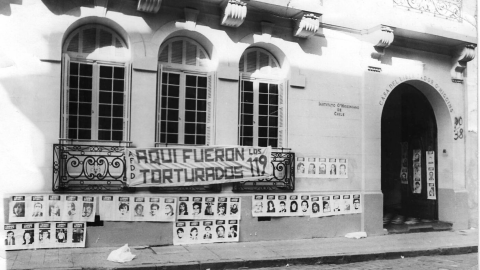

Museum of Memory and Human Rights (1): Chile's national memory institution

Interview: Merve Bakdur and Noémi Lévy-Aksu

The Museum of Memory and Human Rights (MMDH) is the partner of our project Connecting Past to Present, supported by the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience. The museum, which hosts a main exhibit as well as temporary exhibitions, was created to commemorate the violations of the right to life and human dignity committed by the state of Chile between 1973 and 1990, under the rule of Pinochet. It organizes a wide range of activities to foster intergenerational dialogue and stimulate critical thinking and discussions on citizenship, human rights, and democracy today.In our interview with Maria Fernanda Garcia İribarren, the director of the Museum, and Francisca Davalos Bachelet, in charge of international relations, we discussed the mission of the museum, its activities and its efforts to mainstream gender.

What is the mission of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights? How would you describe its outreach? Can we define this museum as an activist institution?

The mission of the museum is to commemorate the victims of the dictatorship, to restore their dignity. As a product of the transitional justice process, the museum is part of the efforts to uncover the truth about this period and make it visible and understandable for the future generations. At the same time, by remembering this past, we can engage in a deep reflection on democracy and on human rights, understanding that human rights are not guaranteed and working for the non-repetition of these violations.

The museum attempts to reach the whole society but the survivors and the victims’ relatives compose the first circle of its relations. They are the ones who make possible the museum by their donations. Indeed, the museum does not purchase anything, we only rely on donations of archives and other materials by the survivors and their relatives. We continue to increase the collections of the museum. Of course, we cannot exhibit everything but we regularly review our main exhibition and temporary exhibitions allow us to work more closely with the local communities.

The second circle gathers organizations and activists in the area of human rights and memory. With no doubt, we are an activist institution. Together with contributing to the better understanding of the dictatorship, we are addressing human rights violations happening nowadays in Chile and other countries, and we struggle for equality, for the rights of women and LGBTİQ+ individuals. We consider that the preservation and transmission of memory is a collective task, which cannot be separated from a broader commitment to human rights.

However, our activism differs from the activism of the former places of torture turned into sites of memory. As a national institution, the museum has a specific scope and mission, which also limits the scope of its activism. In this respect, the sites of memory are much more activist than we are.

What is the relationship between the museum and the state? How do you evaluate the official politics of memory in Chile?

The museum depends on a non-profit private foundation, but it receives funding from the state through the ministry of culture, arts and patrimony, The funding is discussed every year in the Congress (the House of Representatives and the Senate) because it is part of the national budget law. In this respect, we are always dependent on the political dynamics of the country.

The museum mission is to reflect the truth established by the commissions of the transitional justice process. Obviously, these commissions were not perfect, they had limits. For instance, they were little sensitive to gender and to how people were targeted by political violence due to their gender identity. Other things could have been done, but it was also important to hold these commissions early on after the end of the dictatorship. The main limit of the process has been the impunity of the perpetrators, still ongoing. Nowadays, we use the concept of “biological impunity”, meaning that either survivors or perpetrators are dying, ending the possibility to access truth and justice.

The state policy of memory in Chile is fragmented, touching upon many different aspects of the social life. For instance, one program gives priority to survivors and victims’ relatives in the health system. Another example is that former political prisoners and survivors of torture receive a life pension. The museum is another expression of the commitment to the state to the memory politics. It is important to find ways of emphasizing justice and of making visible other ways of resistance in the official narrative. The museum is currently developing a new area on justice.

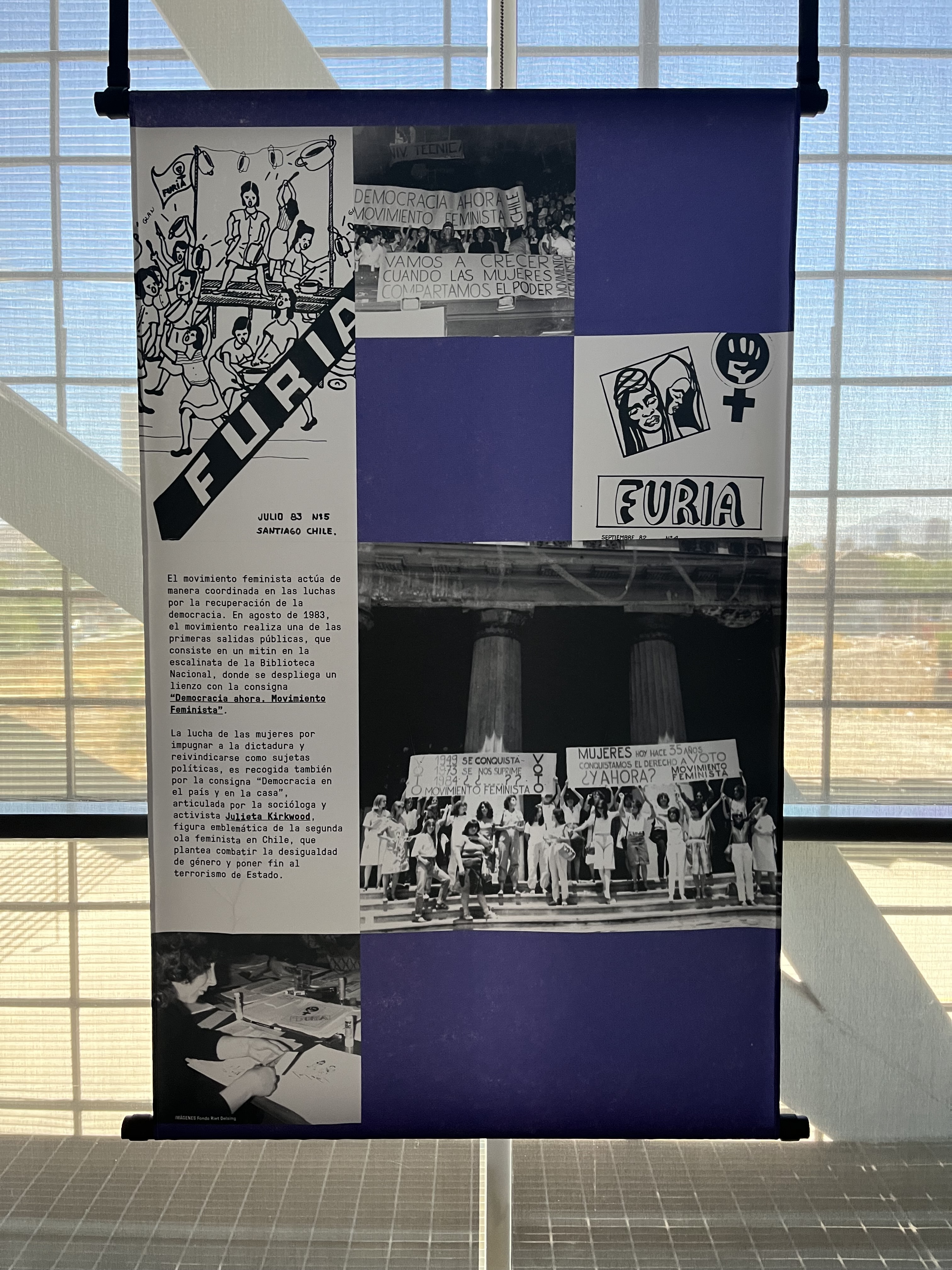

In the last years, the museum had developed the program “Memory and Feminism” and given more visibility to the experience of women and LGBTİ+ individuals. What are the main aspects of your work on gender?

The line “Memory and Feminism” aims to mainstream gender in our exhibition and our activities. While the majority of victims of the dictatorship were men, women were also targeted by the repression. Around 200 women were killed or disappeared, and many more were political prisoners and victims of torture. The museum has a special emphasis on sexual political violence, which was specifically directed to women, although it could also affect men.

During the dictatorship, women had also a leading role in the fight to know the truth and find the disappeared victims, as mothers, wives or daughters. Women kept protesting the dictatorship and struggling for democracy. As much as suffering, the museum attempts to emphasize the role of women in resistance, through different channels. For instance, in neighborhoods and local communities, women played an important role during the economic crise of the 1908s in Chile. They organized kitchen soups for food distribution and they turned arpilleras (embroidery) into powerful social networks. Actually, they were able to create a much more unified movement than the political parties did.

Since 2023, the museum has been working on women’s memories, collecting their stories and archives, enriching its collection and transforming its main exhibit to integrate their experiences. We held focus groups with women to understand what was lacking in our approach and increase the inclusivity of our narrative.

Relying on this experience, we have started to work with the LGBTİQ+ individuals who lived during dictatorship, but also on the younger generations, to understand their experiences and the specific forms of violence they were victims of. It takes time to build trust but it is very important to restore the gender identities that were erased in the truth commissions. Although political identity was the main target of the dictatorship, the new political order that put family and the military first was also hostile to the LGBTİQ+ individuals. Their stories have not been told, and the museum can be a space to transform this narrative.

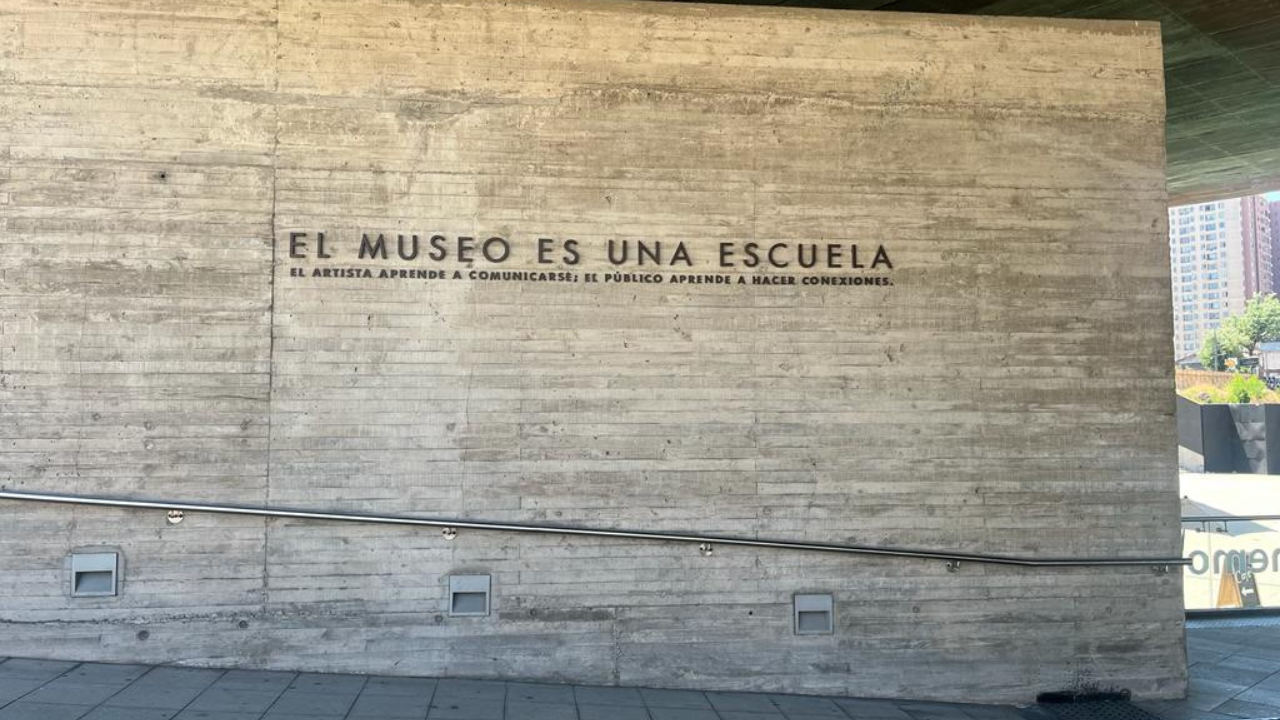

* The photograph used at the beginning of the interview is from the entrance of the museum. Here it says: “The museum is a school. The artist learns to communicate; the public learns to connect”.