Museum of Memory and Human Rights (2): Museum as a learning space

Interview by: Noémi Lévy-Aksu

The Museum of Memory and Human Rights (MMDH), our partner for the Connecting the Past to the Present project supported by the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, was founded in 2010 to commemorate the human rights violations committed during the dictatorial regime that ruled Chile between 1973 and 1990. In this second interview, conducted with the Director of the museum’s Education Department Sandra Piñeiro Fuenzalida, and mediator Francisco San Martín Sepúlveda, we learned more about the methods and objectives of the guided visits and workshops organized by the museum. We were particularly interested in their attempts to connect past to present and foster youth engagement with the memory field.

Could you explain your approach and methods in the mediated visits and workshops?

The use of sources is central to our work. In the experience of mediation, our participants are not only confronted with a discourse, with a script proposed by the museography but also with the document itself, which is also a historical testimony of what has been experienced, whether it is a letter, an article, or a picture. The document provides evidence about the past, but it also triggers different memories among the audience. We try to hear and discuss these memories and establish a dialogue between the historical narratives and the individual memories.

There is a moment where the participant appropriates the documents or appropriates the content to create something, depending on the age of the participants and the dynamics of the group. For instance, we worked with students on the photographs of Charles Gerretsen, the photographer who documented the coup with pictures of the bombing of the governmental palace in 1973, some of which were published by a magazine in France in the 1970s. We invited the students to reflect on the choice of pictures, and the power dynamics they expressed. We asked what their own choices of pictures and headlines would have been, and something very interesting came up as the students responded to this experience. It was their problems that took shape through these images and the headlines they chose. In the end, the workshop fostered a very creative participation, where the participants built their own narrative from their experience so that we have many diverse discourses or narratives in the same group.

We also try to develop educational materials and games, which we can use in the workshops. For instance, we developed the board game 31 Minutes, which opens a space for discussions on human rights, or the “Journey through the Voices of the Dictatorship” application, which was prepared in collaboration with Alberto Hurtado University. These support materials are important but we have limited resources, so we privilege collaborations with other institutions to develop them.

Currently, the area of education of the museum is being restructured. We are assessing our fourteen years of activities in order to determine what has worked the best in our work and in which directions we should develop our activities. For instance, the themes of denialism and impunity are of great relevance, as well as the visibility of women and minority groups, such as the natives. As a whole, our approach has become more inclusive over the years.

Part of the museum's permanent exhibition is dedicated to torture and gross human rights violations. How do you discuss these issues with a young audience without traumatizing them?

First of all, most people tend to think that because they are children they don't understand or know what happened. We constantly realize that they do know a lot and they have a lot of questions. They are continually learning about death and destruction through the press, video games, and other sources, so it is important not to infantilize them, but to find ways of addressing these topics in a way that is not traumatizing. We work in close collaboration with their teachers, to understand their expectations and sensitivity.

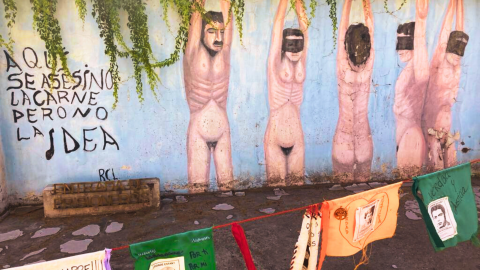

As a museum, we are very careful to avoid falling into morbidity and showing violence per se, as it is sometimes done elsewhere in the world. The objective of the exhibition is the denunciation of the violence which happened. We need to name it, contextualize it, and open a debate on the past and the conditions for non-repetition.

The vast majority of the young visitors have some prior knowledge about the dictatorship. Human rights education, the history of the dictatorship, and civic education have been integrated at different levels of the school curriculum. In general, they have some familiarity with the human rights violations perpetrated during the dictatorship. We work on this prior knowledge to go into more details, and to develop critical thinking. We did come across a group of students who did not differentiate between Pinochet and Allende, but this is an exception. Yet, bringing the students to the museum relies on the initiative of their teachers, so we are aware that there are also schools or localities we never see at the museum.

How is it possible to develop an intergenerational dialogue on these issues?

When we bring together teachers, students, parents, children, institutions, and the general public, different generations come together with their own experiences and memories. Although we tend to work with homogeneous groups in terms of age, the dialogue between the mediators, the teachers, and the young participants is already a form of intergenerational dialogue.

In general, in Chilean society we are not talking a lot about these issues. Silence is something very impregnated in our dictatorial culture, not only because of the silence of the perpetrators but also because of the brutality of the repression and the fact that victims directly affected have not always been able or willing to tell their families what they endured. This is why places such as the museum are so important, to break this silence and enable people to understand what happened to their relatives, and to the generation affected by the dictatorship.

We could do more to develop different forms of intergenerational dialogue, for instance maybe working with families and bringing together three generations of the same families. This has been done for documentation and collecting testimonies, but we have not worked on this approach from the perspective of mediation or education.

How do you connect the past to the present? And how does the current socio-historical context shape your work?

During the mediation, there is always a moment when we invite the public to connect the historical period of the dictatorship with the present, with their reality. This is an invitation to expand the awareness about the past to the present, in which each one of us as a citizen has an active role to play in the defense and protection of human rights. The “never again” is not enough, we also want to emphasize “today more than ever.”

The socio-political context has an important influence on the way we present the past. The women’s movement, the social protests, and the constitutional movement have led us to reconsider our approach. We are sensitive to social demands, which helps us adopt a more inclusive perspective, both in the main exhibit and in the mediation experiences. For instance, there is now much more on women’s agencies, and more radical forms of protests during the dictatorship, such as the Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front, have been included. Our audience is also shaping our approach. In the groups of pupils who visit us, many children come from migrant families or who are migrants themselves, so the issue of migration has taken a greater importance in our work, which is reflected in the temporary exhibitions for instance.

Although our focus remains on the period between 1973 and 1990, inequalities and threats to human rights continue nowadays, so it is important to invite the visitors to reflect on this context and to discuss what can be done at the individual and collective levels to avoid the repetition of the crimes. There is tension there because the museum has to comply with its mandate, which is to make visible the victims of the dictatorship, as well as to emphasize the importance of respect and tolerance to guarantee non-repetition. Its chronological scope is very clear and we need to relate to the past when we integrate the present. Yet, somehow in our approach the past is always in dialogue with the present, and therefore with the future.

* The original language of the conversation Noémi Lévy-Aksu had with Sandra Piñeiro Fuenzalida and Francisco San Martín Sepúlveda was Spanish. This text is the translated and edited version of the transcription.