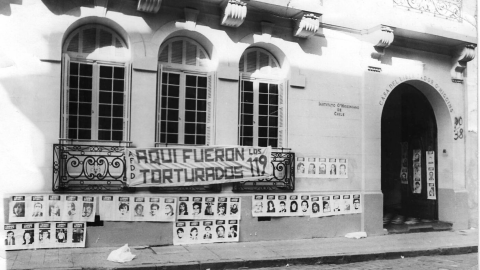

Reclaiming the memory of dictatorship in Chile (2): Casa Memoria José Domingo Cañas

Interview by: Noémi Lévy-Aksu

Located in the Chilean capital of Santiago, Casa Memoria Jose Domingo Cañas 1367 was known as Cuartel Ollagüe and was used as a center of detention, torture, and execution by the National Intelligence Directorate (DINA) between 1974 and 1978. The majority of the detainees were members of the Revolutionary Left Movement. While the house was demolished in 2001, the efforts to reclaim the site were finally successful and resulted in the building of Casa Memoria, a space of memory and activism.

In our interview with Marta Cisterna Flores, the executive director of Casa Memoria whom we met during our field visit in January, we discussed the process of reclaiming the site, the limits of the official policy of memory in Chile, and the activities of Casa Memoria in the area of education and human rights.

Like other places of detention, torture, and execution located in Santiago, the Casa Memoria Jose Domingo Cañas became a place of memory through the struggle of victims and activists. What were the goals and meaning of this recovery process, and how does it continue to influence the current activities of the Casa Memoria?

The recovery process was initiated by the people of the neighborhood. Their objective was to avoid the loss of the memory of what happened. They wanted this place to be a space that revealed what had happened because they were witnesses.

This was the first goal, but then this was mixed with the objectives of a broader process of recovering a multiplicity of sites in Chile. At the same time, there were demonstrations, occupations, and initiatives to recover other sites such as Londres 38, the Santa Lucía Clinic, and the National Stadium. We used to meet the same people at these different sites: we were in José Domingo Cañas on Wednesday, Thursday was the day of London 38, and so on. I am not sure we all had the same objectives there. The common goal was to recover these spaces and turn them into sites of memory, but we didn't know clearly at that time what a site of memory meant.

To what extent has this process influenced our activities in the present? First, we have indeed become a site of memory, as the local community wanted. Besides, a large part of our work aims at bringing the community closer to the site, involving the neighbors in our work, and encouraging them to tell us their memories. In this respect, the memory site is also a community space.

Most of your activities focus on current political and social issues in Chile. What is the connection between your memory work and current activism?

We believe that the present cannot be understood without sites of memory. The site of memory represents the political project that was destroyed by the military coup, but also the dreams and the ideal of building a new world. Describing the site through the different stages it went through allows us to understand the roots of the current political-social-economic model.

On the other hand, the serious human rights violations that were committed in this place should have generated a state policy around non-repetition, which is the basis of transitional justice. Yet, this non-repetition has not been possible, we cannot talk about human rights violations in the past, and this is why we are so connected to the present. Despite having such strong evidence as the sites of memory in Chile, there is still torture, there are still political prisoners. A few years ago, we also began to talk about social, economic, and cultural rights because our comrades, who were held in José Domingo Cañas, struggled not only for civil and political rights but also for social, economic, and cultural rights. They aspired to a new social order where everyone could enjoy rights and the inequality gap would be reduced.

In sum, we cannot talk about the site of memory without looking at the present, and we cannot move forward without memory. For us, this is the great contribution of the sites of memory, because otherwise, they would only be a dead museum where we tell a sad story. For us, the site has to contribute to the guarantees of non-repetition, it has to question the State in terms of its commitment to transitional justice, so that those practices that occurred in José Domingo Cañas may not be repeated in other spaces.

During the transitional justice process, the State recognized responsibility and developed a policy of memory. But I also know that you are very critical of the state's policy in this area. How would you evaluate the role of the state from the recovery process to the present day? And what are the limits to this official memory policy of Chile today?

For a long time, I used to say that Chile did not have a memory policy. Now I acknowledge that Chile indeed has a memory policy but I would add that this is a bad policy. Rather than a comprehensive policy of memory, there have been specific gestures that have responded to demands around the transitional justice process.

Generally speaking, the memorialization process in Chile first came from civil society, not from the state. It was initiated by organizations, survivors, and relatives. There is no site that the state has recovered without civil society initiatives. Among the 1132 sites that are registered, fewer than 100 have been recovered and all have been reclaimed by civil society. Among them, many were demolished, and the State only granted their property to the civil society initiatives without any significant economic contribution, technical support or expert advice to support these initiatives.

As for the official memory promoted by the State of Chile, this is the memory of the horrors of the dictatorship, and it was somehow an obligation linked to the transitional justice process. The Museum of Memory and Human Rights (MMDH) was a product of this context and it has important limits. Its periodization ending with the 1988 Chilean presidential referendum reflects the official discourse on the return of democracy. In addition, it obliterates the memories that make people uncomfortable, such as the processes of resistance and the frontal struggle against the dictatorship.

Another example is the Memorial of the Detained, Disappeared, and the Politically Executed in Santiago General Cemetery. The victims’ relatives demanded that the names of the victims be inscribed on a huge wall, with niches that could host the remains of the disappeared if they were to be found. Yet the state authorities have included in this list the names of the perpetrators, who were killed in clashes, or alleged clashes. This follows the logic of the Rettig report issued by the first truth commission, which applied what the Argentinians call “the theory of the two demons,” equating acts of political activism with state terrorism. It incorporates perpetrators within the victims and talks about political movements in Chile as if they were terrorists. Not everyone knows that, but this wall still includes the names of perpetrators. This is what I mean when I talk about bad memory policy.

Another problem is that the state applies the neoliberal logic in its memory policy, which excludes some sites and puts other sites in competition with each other for funding. The criteria are not clear but there are great inequalities of funding between the sites, for instance, Jose Domingo Cañas receives much less funds compared to Villa Grimaldi or Londres 38.

I know that Chile is ahead in terms of sites of memory compared to other places. I understand that there was an important social conquest here, but this should not prevent us from criticizing the state. For instance, there was a reform of the curriculum to include the period of the dictatorship, but teachers in Chile have insufficient information on human rights or pedagogy of memory. The same goes for health professionals; they should get special training on human rights and the issue of torture. We now have an older generation in Chile, who went through situations of political imprisonment and torture, and the professionals who are treating them have no idea of the approach they should adopt when dealing with them. For instance, when treating someone who can't go to the dentist because of the torture with electricity they went through.

You work a lot with the young public. To what extent are younger generations in Chile aware of the dictatorship? And what are your methods to actively engage them with your site of memory?

I don’t think there is a deep understanding of the dictatorship among the youth. They have seen the famous images of the coup, like the bombing of Palacio de La Monedad (the seat of the president of the Republic of Chile), but they know little about the different aspects of the dictatorship. We receive many visits from students brought to the site by their teachers. They always come back the next year, because our methodology actively involves the young visitors in the different moments witnessed by the site, making the connection with the present.

For instance, when talking about the 1960s, we tell them about the young people of those years, we show them the clothes they wore and the music they listened to, and we ask them about their own tastes. From there we come to the dreams of the young people of that time and ask the young visitors about their own dreams. We continue the narrative until we reach the point when these young people have finally disappeared. We want them to understand that the dictatorship wanted to destroy the political projects of these young people. We also make them choose someone within that memorial and explore their story, from their childhood to their disappearance.

Around 2015, we also created a program called Youth, Human Rights, and Memory. We started to work with a secondary school where more than 50% of pupils are migrants. The school partnered with the University of Chile to work on methodologies in human rights, memory studies, and critical pedagogy. The rules of coexistence of the school were also changed and we encouraged the creation of a Human Rights Committee composed of different actors of the school, such as teachers, administrative staff, students, and students’ parents. The program has been going on for several years, yet it could not grow since we don't have funding. However, once a year we have a small meeting, we gather students from different schools and we stay three days in a region of Chile, organizing memory tours and discussion sessions with the youth. The aim is not only to work on the pedagogy of memory but also to provide these young participants with tools to better understand their society.

How do you think that sites of memory, in particular Casa Memoria, contribute to the struggle for justice?

That is a complex issue because I think it is not only a matter of intentions, but also of resources. José Domingo Cañas, with its limited resources, chose to contribute to the guarantees of non-repetition with the monitoring of human rights: we conduct observations and issue reports on the human rights situation in Chile. Recently, we presented our shadow report to the UN Human Rights Committee which was evaluating Chile, social and political rights. Our report denounces the half-statute of limitations that is being applied to the perpetrators and the lack of progress made in the judicial cases. Our advocacy work is useful because it provides concrete elements on the situation of impunity. The human rights training we provide should also be seen as a contribution to justice. As a site of memory, we consider we have a political mission and that our struggle for justice in the present is also connected to history.

We are also one of the few sites of memory that are involved in the National Search Plan launched by the state. We brought materials from the other search plans existing in the region and made connections with relevant initiatives, such as the forensic anthropology team of Guatemala, which has been a pioneer in these kinds of searches. However, the name of the National Search Plan is quite misleading. The official objective of the search plan is to centralize the information that is available on different sites to reconstruct the trajectories of the disappeared detainees, from the moment of their kidnapping to their disappearance. Our main demand is a decree that would declassify the archives of the Armed Forces because people who were supposed to speak have already spoken. How will we know what has happened to our comrades if these archives are not opened?

We thus fear that this plan may generate a re-victimization and that the high expectations of the relatives may not be fulfilled. At best a central database will be created, but this does not mean searching and finding the disappeared. In other words, the comrades in the north of Chile will continue to search the desert, to see if they can find a bone. There are also still hundreds of hectares to be searched in the former Colonia Dignidad, in the South of Chile, where German settlers actively collaborated with the dictatorship to torture, assassinate, and disappear political prisoners. If you do not start a systematic search campaign in these regions, how can you talk about a National Search Plan? I find this situation outrageous and frustrating.

*The original language of the conversation Noémi Lévy-Aksu had with Marta Cisterna Flores was Spanish. This text is the translated and edited version of the transcription.

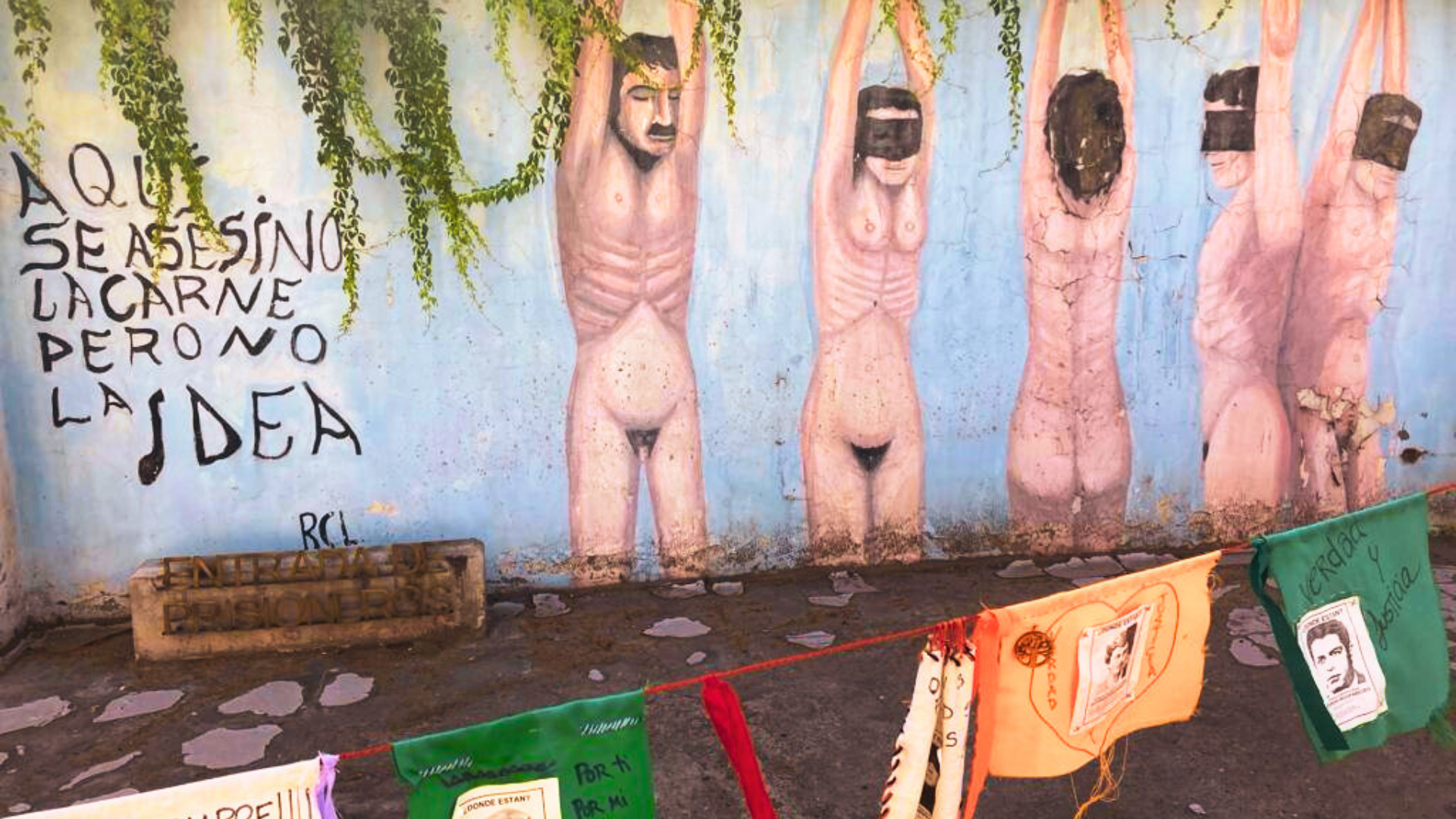

**The image used at the beginning shows a mural from the front yard of Casa Memoria José Domingo Cañas. The text seen on the wall reads, “Bodies were killed here, but not ideas.”