Reclaiming the memory of dictatorship in Chile (1): Londres 38

Interview by: Noémi Lévy-Aksu

Londres 38 was one of the memory sites we visited during our field visit to Santiago between 7-13 January 2024. Located in a central district of Santiago, the house was used as a place of detention, torture, and execution after Pinochet’s military coup. The repression particularly targeted the members of the Revolutionary Left Movement. In 2005, the building was registered by the state as a historical monument. Today, Londres 38 is known as much for its memory work as for its political activism. It organizes educational workshops and actively contributes to legal interventions and documentation. In our interview with Maíra Máximo, a guide and facilitator at Londres 38, we discussed the process of reclaiming the site, the relation between memory work and social activism, and their contribution to the struggle for justice.

Like other centers of detention, torture, and execution in Santiago, Londres 38 became a place of memory through the struggle of victims and activists. What were the goals of this process of reclaiming the site? And to what extent does it continue to influence the current activities of Londres 38?

This process started when this place was being used as a clandestine detention center in 1974, by the DINA, the National Intelligence Directorate, to repress the leftist activists, particularly the Movement of the Revolutionary Left (MIR). Relatives of disappeared activists, particularly their mothers, heard about the place and started to knock on the door, to ask about their children who were detained. After the house was turned into the O’Higgins Institute for Military Research in the 1980s and the 1990s. Victims’ relatives and civil society activists put up banners, held protests, and chained themselves to the building to denounce its former function and ask for its recovery.

The turning point of this mobilization occurred in 2005 when the house was registered by the state as a historical monument and protected against destruction or modification. The Londres 38 collective, an informal group of victims’ relatives, survivors, and activists, then concentrated on reclaiming the house and making it open to the public. This was a contentious process, which involved many tensions with the state, which intended to create an Institute for Human Rights, with no social participation, but also between the different actors of the collective, as some were opposed to getting funding from the state.

Finally, in 2010, the Londres 38 collective got the right to operate the building as a site of memory. The main idea was to open the site to the public as a way to understand and denounce the past atrocities, but also to reflect on the present. There was also a judicial objective, as the house went through expert reports and archaeological surveys, to look for evidence of torture and state violence and to contribute to uncovering the truth about the dictatorship.

To sum up, reclaiming the site has been a long process, starting in the 1970s and continuing nowadays. All over this time, the networks and alliances formed, as well as the tensions and divergences, have been most important in shaping Londres 38 as a site of memory and activism.

Londres 38 is a site of memory that commemorates the victims of state violence. However, many of its activities are oriented towards current political and social issues in Chile. What is the connection between your memory work and your current activism? What are the main areas of this activism, and who are the social actors with whom you collaborate?

From the very beginning, when we reclaimed the building, our main idea was to think about memory from the present. We consider that there are more continuities than ruptures between the dictatorship and nowadays. State violence and state terrorism continue to occur in the present. They are based on structures that were constituted or consolidated during the dictatorship, and which did not undergo any significant modifications during the period of democratic transition. For example, the Constitution of 1980, which was signed by Pinochet, is still the Constitution in force today.

Moreover, the same political class, the same elites, and the same people who supported the dictatorship continue to be part of what sustains the political and economic system in Chile. This situation involves a lot of denialism concerning the dictatorship and a lot of impunity about the crimes committed by the regime. It also means that human rights violations are still occurring in the present. For instance, during the social outbreak in 2019-2020, around 40 people were killed and 500 people lost their eyes due to the excessive use of force by agents of the state, carabineros, or soldiers.

In that sense, it is important for us to think about the political, social, and cultural legacies of the dictatorship and to collaborate with organizations that are not directly related to the issues of memory or the dictatorship, such as feminist organizations and grassroots initiatives.

Let’s talk a bit more about the role of the state in this process. Chile went through a process of transitional justice and, during this process, the State recognized its responsibility and took measures for the memorialization of the crimes committed during the dictatorship. As you said, Londres 38 is one of the sites that are recognized and protected as historical monuments. Seen from Turkey, this seems like a great achievement, but you are also very critical of this process. Could you comment on the role of the State from the recovery process to the present day and the limits of the official policy of memory today in Chile?

The relationship between civil society and the State has always been complex since the end of the dictatorship. First, when we talk about the democratic transition, we take for granted that the dictatorship officially ended in March 1990, when Pinochet left power. Yet, Pinochet continued to serve as Commandier-in-Chief of the Army until 1998, when he became senator-for-life. In the 1990s, the military still had a lot of power. Only from 1999 onwards did the army assume some responsibility for the crimes that were committed. The reports of the truth commissions, the Rettig Report (1991) and the Valech Report (2004) were of course important landmarks, but there is still a lot to do to uncover the truth. For instance, the testimonies obtained during the investigation of the Valech Commission have been classified and will remain confidential for fifty years, until 2054. Consequently, the names of the perpetrators remain secret and the records cannot be used in trials pertaining to human rights violations.

Let’s also emphasize that no site of memory in Chile has been reclaimed on the initiative of the state. Only civil initiatives and collectives made possible the recovery, and the state was often an obstacle to them. In the case of Londres 38, although our struggle enabled us to finally be recognized as a historical site and get funding for our activities, we are now fighting for an architectural restoration of the house, which suffers from many structural weaknesses. We have still not been able to get the necessary permissions, which means that we may have to close our doors as the building may become unsafe for visitors.

In short, we are the interlocutors of the state, but there are still many tensions and our relations depend a lot on the political context. Last year, which corresponded to the 50th anniversary of 1973, the progressive President Gabriel Boric launched a “National Search Plan” to search for people who disappeared during the dictatorship. Civil initiatives such as Londres 38 are associated with this plan, yet things progress very slowly and insufficient funding is allocated to this search.

On the other hand, today it is part of the rhetoric of the conservative parties to claim that the human rights organizations and memory sites lie, that they are useless or harmful initiatives abusing public funding. In this respect, sites of memory are vulnerable, they could lose their funding if a right-wing majority came back to Congress. Londres 38 is relatively in a more secure situation, as it is one of the few sites that are protected and funded under the National Monuments Law, yet Chile still lacks a legal framework that would enshrine all the sites of memory and spare them from hostile political interventions.

Let’s come to your educational activities. You have been organizing memory workshops for a long time. What are the objectives of these workshops and their methods to actively engage the participants? To what extent is Chilean society, particularly the youth, interested in confronting the past?

Since the opening of Londres 38, we have designed our memory workshops as dynamic events with approaches and methodologies inspired by popular education and the critical pedagogies of memory. Memory is an entry, which we use to create a space for reflection, discussion, and collective knowledge production, based on the participants’ different experiences of the past and present.

In the last few years, we started to work mainly with young people, teenagers or university students. We address topics related to state violence, arrests, and disappearances, but also more generally the continuities of the dictatorship in the present, in the economic, social, and cultural areas. We are also partnering with women’s organizations and migrants’ initiatives for these workshops, and we have been able to develop collaborations with municipalities and local initiatives in different neighborhoods of Santiago.

Most people who come to Londres 38 are young people between 15 and 29 years old. In many cases, they experience difficulties in talking about the dictatorship and political issues in their family or at school, and they look for spaces like Londres 38 to learn and discuss freely. Sometimes we have to develop strategies to overcome the reluctances of the establishment or the institutions. For instance, we refer very clearly to the objectives of the curriculum of the Ministry of Education when developing our activities with the youth. We also work a lot on language, particularly when working with municipalities, to avoid alienating people who have prejudices against civil society initiatives. Thus, in one case, when we participated in a workshop at a municipal institute whose director was a retired army officer, we relied on official data and state documentation related to the dictatorship to make it possible to discuss these issues.

Finally, I wanted to ask you how sites of memory, such as Londres 38, contribute to the fight for justice. How do you articulate your struggle against impunity and your commitment to social justice?

Londres 38 is one of the few memory sites that have an active line of work related to the struggle against the impunity of the perpetrators. This is little visible in the physical space of the exhibition, mainly due to museographic decisions and technical constraints. Yet, we have an active truth and justice commission, mostly composed of lawyers, who are actively involved in legal cases related to Londres 38. We are also active in the digital sphere. Thus, the digital archive of Londres 38 offers comprehensive legal documentation, including the testimonies of the perpetrators before or outside the courts. We have also carried out digital campaigns to hold the perpetrators accountable. The last one was about the perpetrators who are fugitives: we disseminated their pictures, the charges against them, and information about their whereabouts.

Our fight against impunity is also directed towards human rights violations in the present. For example, Londres 38 is intervening with other organizations in cases of human rights violations perpetrated during the social outbreak of 2019-2020. Unfortunately, we see a permanent state of impunity, relying on deep alliances between the state apparatus, conglomerates, and local powers. This is a legacy of the transition period, where there was a consensus to protect certain institutions and structures from accountability.

Together with this fight against impunity, the objective of Londres 38 is transformative. This is directly related to the legacy of the victims of the dictatorship, who were activists attempting to transform society and struggling for social justice. We continue their struggle, trying to hold accountable the perpetrators of the human rights violations they were victims of, but also struggling for a fairer society.

*The original language of the conversation Noémi Lévy-Aksu had with Maíra Máximo was Spanish. This text is the translated and edited version of the transcription.

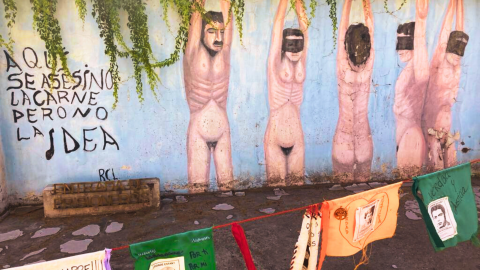

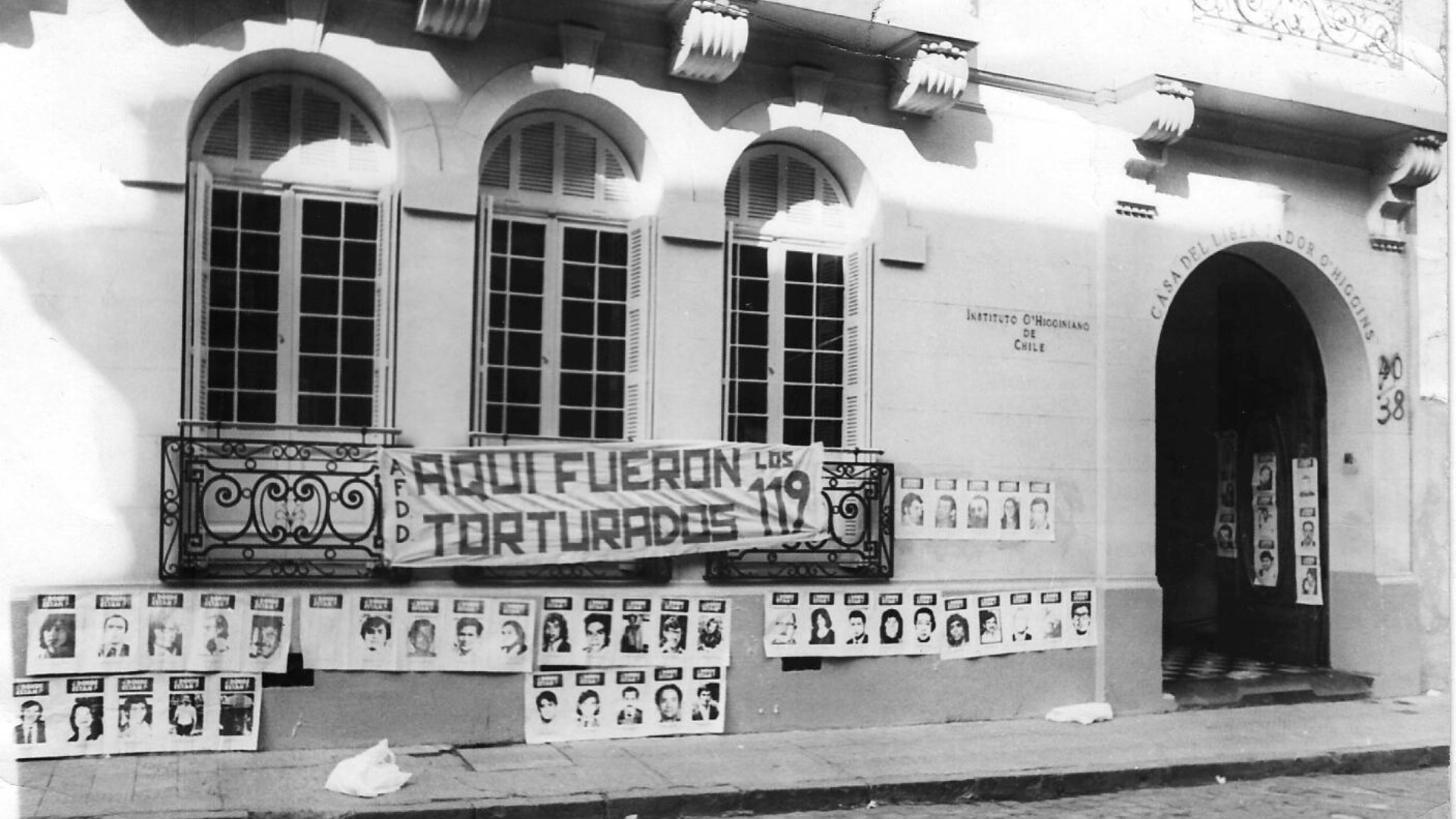

**The image used at the beginning of the interview is taken from the Londres 38 Digital Archive. According to archival sources, this photograph from 1980 shows a banner reading “Aquí fueron torturados los 119 / 119 people were tortured here” hung on the building that was used as O’Higgins Institute for Military Research at the time.