Reclaiming the memory of dictatorship in Chile (4): Iran 3037

Interview by: Noémi Lévy-Aksu

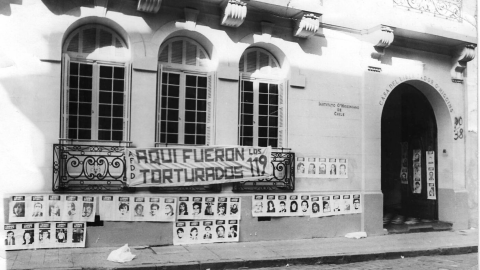

Iran 3037 is a memory site built in the 1950s and located in a residential neighborhood of Santiago. It was used by the DINA (National Intelligence Department) between 1974 and 1977 as a secret place of detention, torture, and execution, under the name Cuartel Tacora. The place was also known as “Venda Sexy” and “Discoteque”, as it witnessed the systematic use of sexual violence against the detainees, while loud music was used to cover the victims’ screams. 33 victims were killed or disappeared there. The process of reclaiming the site is still ongoing; however, the collective of survivors and victims’ relatives have established a “Memory Grove” in a small park nearby, to commemorate the victims and interact with the neighborhood.

In our interview with three members of the collective, Maria Luisa Flores, Montserrat Figuerola, and Alejandra Holzapfel, we discussed the process of reclaiming the site, as well as their efforts to foster the active engagement of local communities with their memory work. We also asked Alejandra Holzapfel, a survivor of the site, about her commitment to hold accountable the perpetrators and contribute to the reclaiming of the site.

Unlike other sites of memory we visited in Santiago, Iran 3037 is a memory site still in the process of being recovered. Why has it been such a long process? Could you tell us about the main stages of this struggle for this recovery and the obstacles you had to overcome?

Reclaiming Irán 3037 has been a long process, due to multiple factors. On the one hand, the silence around the spaces of kidnapping, torture, and extermination did not allow an early identification by the State, which meant a significant delay in the recovery and protection of the property. Secondly, many years after the dictatorship, there was no political will to recover the property, which passed from owner to owner, undergoing irrecoverable modifications. Finally, when the State showed interest in recovering the property, the owner engaged in a bargaining process, to obtain a sum of money much greater than what the State could finance. The current government is committed to fighting to reclaim this space. This is why, after failing to purchase the place in the previous years, the State was able to expropriate the owner without the need to negotiate. This entire process has been very long and exhausting for the organization and the survivors.

When you recover this place, what will be the mission of the memory site? Have you already an idea of the spatial organization and activities you would like to implement there?

The corporation Iran 3037 was created to rescue and disseminate resistance and individual and collective memories of state terrorism and sexual political violence, through the recovery and management of the former clandestine kidnapping, torture, and extermination center Venda Sexy. Our work will be articulated around three main themes: Memory, Resistance, and Justice; Participatory Community and Territorial Action; Gender, Feminist, and Dissident Perspective.

Our activities already include research and archive work to investigate, study, collect, and preserve the memories linked to the Iran 3037 Memory Site. We are also working on the development of a program of commemorative, artistic, and cultural activities for the visibility of the memories associated with the Iran 3037 Memory Site, based on long-term work with relevant communities and local actors. Finally, the site will host a program of education in human rights and pedagogy of memory, as well as other dissemination activities.

When we visited you in the small park of memory close to the house, we were very impressed by the spontaneous participation of neighbors in the conversation and their support of your action. How did you manage to achieve this social integration? Have you also faced negative reactions from the local inhabitants? To what extent do you think that the efforts to confront the past can reach the broader Chilean society?

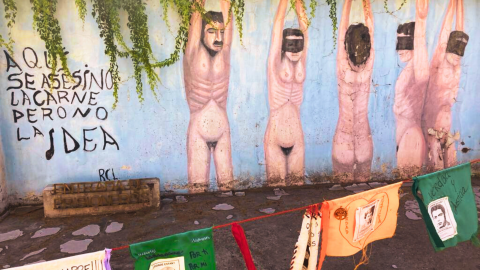

The process we have carried out in Plaza Arabia, in front of Iran 3037, has been very organic. Gradually, we managed to form a group of women who began to meet to weave large red cloths, which represent the spilled blood of women in the world and in Iran 3037. It was a small gesture, but it began to strengthen the social fabric of the territory, and more and more neighbors came to meet us. Spontaneously, neighbors who also felt welcome in our struggle did so.

We have had negative experiences as well. The memorials on the corner of the house have been vandalized, the last time less than a month ago. These events respond to a series of denialist actions, which seek to erase the memory of the place and therefore damage the processes of recovery of memories and the struggles for human rights. However, memory is disobedient and persists in the struggle of every one of us.

To overcome the barriers of denialism, it is necessary to establish these discussions in each of the educational communities of the country, to make it impossible to say that this did not happen. This requires public policies of memory and the protection of human rights. Historically, in Chile, organizations and civil society are the ones who have identified, recovered, protected, and managed memory spaces. This makes their fight unequal, compared to other political forces that have immeasurable resources. As long as the State of Chile does not protect Memory spaces in a transversal way, it will continue to be the organizations, survivors, family members, and activists who carry out this fight.

Iran 3037 is known for the systematic use of sexual violence against political activists, particularly women, detained there. Alejandra, as a survivor of this place, could you tell us about your legal struggle to hold accountable the perpetrators? And does your participation in the struggle to recover this place contribute to another form of justice?

In 2013, I [Alejandra Holzapfel] was one of the three female comrades who filed the first complaint regarding political sexual violence with kidnapping carried out by officials of the State of Chile. On October 3, 2023, judge Mario Carroza convicted Raúl Iturriaga, Manuel Rivas, and Hugo Hernández, for perpetrating the crimes of kidnapping and use of torture perpetrated to the detriment of Alejandra Holzapfel, Laura Ramsay, and Clivia Sotomayor. The three perpetrators received an effective prison sentence of 15 years and one day, and the plaintiffs received financial compensation.

This legal fight and the struggle to recover this place are an obligation for me, for those who fell and forcibly disappeared. Reclaiming the site is a way to heal and redefine our experiences, transforming them into a creative, individual, and collective movement. I do not forgive, I fight for truth and justice, nothing more and nothing less.

*The original language of the conversation Noémi Lévy-Aksu had with Maria Luisa Flores, Montserrat Figuerola, and Alejandra Holzapfel was Spanish. This text is the translated and edited version of the transcription.